Home

Mission Statement

Editorial Policy

Submission Information

Volume One

Casual Papers

Fort Guijarros

Volume Two

Uncovering Local Art and Industry: The Discovery of Hidden WPA-Era Murals at San Diego State University

Seth Mallios and Nicole J. Purvis

Introduction

Two Works Progress Administration (WPA)-era murals from the 1930s, long thought to have been destroyed during subsequent building renovations, were uncovered in San Diego State University’s (SDSU) Hardy Memorial Tower in August of 2004. Local student artists Genevieve Burgeson Bredo and George Sorenson completed these murals in 1936 at the entrance and in the hallway of the old library at SDSU, known at the time as San Diego State College. Although portions of the murals were obliterated during construction from 1957-59, some of the artwork remained intact. Non-destructive tile maintenance during the summer of 2004 exposed the murals, which have since been resealed behind the lowered ceiling. This article offers a brief social history of WPA artwork and details the images within the two rediscovered murals.

Historical Overview

The United States faced a socioeconomic crisis during the 1930s;

social and economic circumstances surrounding the Great Depression were

devastating for many Americans. In the four years following the record

stock market crash in October of 1929, the country’s gross national

product dropped by over a quarter, construction declined by over 75%,

and the unemployment rate rose from 3.2% to nearly a quarter of the nation’s

work force (Burner 1979:75; Webbink 1960:6-7). Drawing on recent success

in establishing the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA) as

Governor of New York, newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

set his sights on creating federal relief programs (Morgan 1985:232).

He worked with Congress to tailor many of these projects to provide specific

aid for the nation’s 15 million unemployed individuals, many who

faced economic devastation compounded by the continuing failures of banks,

factories, and farms. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), the lead

federal work-relief entity, was established as part of the 1935 Emergency

Relief Appropriation Act (Bourne 1946:4). During their collective eight-year

tenure, WPA projects provided at least part-time employment for nearly

a fifth of the U.S. labor force (Branton 1991:iii).

Artists were among the workforce members who benefited from this new program.

Federal aid for unemployed artists began in 1933, with the creation of

the Public Works of Art Projects (PWAP). A year later the U.S. Treasury

Department Section of Painting and Sculpture absorbed the PWAP. Then in

1935, the Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP) and Federal Art Project of

the Works Progress Administration (FAP/WPA) were united with the previously

established Treasury Department artist-relief entities. Under the WPA,

the Federal Art Project (FAP) funded artists to provide artwork for government

buildings and also loaned various pieces to public agencies and institutions.

Unlike other Treasury Section programs, the FAP awarded projects to artists

on the basis of their individual financial need (Pohl 2002:366). Prior

to being disbanded in 1943, along with many other Depression-era programs,

the FAP created thousands of jobs and resulted in nearly a quarter of

a million works of art. During the 1940s, there was a distinct shift in

national priorities, and World War II replaced the Great Depression as

the primary social concern and recipient of federal funds (McKinzie 1973:179).

Figure 2.1 Donal Hord’s black diorite carving of the SDSU Aztec mascot. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

Upon the inception of the program, WPA offices nationwide were inundated

with requests for work even prior to opening. San Diego was no exception

(San Diego Union, 1 October 1935; sec. 1, 2). The first of over 1,000

WPA-era projects in San Diego County began in October of 1935 with the

construction of a road up Palomar Mountain to facilitate access to the

new observatory. The WPA’s Federal Art Project also produced immediate

employment and artwork for San Diegans. In addition to the creation of

many murals at public buildings, local artists also worked with sculpture,

easel painting, and tapestry. Renowned artist Donal Hord produced many

WPA sculptures, including the 225-pound black diorite carving of the SDSU

Aztec mascot that sits in the center of campus today in the Prospective

Student Center (Figure 2.1). In fact, San Diego State College was the

site of numerous WPA-era projects following its 1931 relocation from Normal

Street and Park Boulevard to Mission Palisades, now known as Montezuma

Mesa. These projects included the construction of Aztec Bowl, the Greek

amphitheater, various classrooms, lecture halls, and walkways along with

a select few mural paintings.

A Depression-Era mindset significantly influenced San Diego State’s

student body during the 1930s. Whether resulting from the widespread economic

hardship or the emergence of WPA projects designed to help counteract

the extended fiscal crisis, those students that attended the local college

expressed an attitude that starkly contrasted with the previous generation.

E. L. Hardy discussed this transformation on his local KFSD radio talk

show on February 23, 1933. He noted that,

The thinking of students of the really thoughtful

type seems to indicate trends toward belief in the necessity of a planned

society, (away from rugged individualism), and toward a re-evaluation

of American ideals—a revulsion from the ideals of the post war [World

War I] boom which emphasized wealth, success and the “career”

man, back to the older American ideals of faith in the common man, equality

of opportunity, and tolerance and respect for the rights of weaker nations

(9:10pm).

In response to widespread unemployment and the apparent overproduction

of engineers, teachers, lawyers, and doctors by universities, San Diego

State students sought “a modernized general education, and an education

that [would] fit into a planned social structure” (Hardy, February

23, 1933, 9:10pm). Instead of attempting to tailor their education specifically

for a singular occupation, students broadened their scholastic inquiries.

They saw their classroom experience less as “education for a job”

and more as “education for personal and social development”

(Hardy, February 23, 1933, 9:10pm).

WPA Murals

Less than two months after his presidential inauguration in March of 1933, FDR received a letter from painter George Biddle, urging him to create federal support for unemployed American artists. Biddle, a friend and former classmate of President Roosevelt’s, explained the context and urgency of this opportunity. Reflecting on parallel events that led to the Mexican mural movement of the 1920s, he wrote, “The younger artists of America are conscious as they have never been of the social revolution that our country and civilization are going through; and they would be very eager to express these ideals in permanent art form if they were given the government’s co-operation” (Pohl 2002:364). The social and political awareness that Biddle described stemmed, at least in part, from the dramatic changes and hardships endured locally and globally. These themes inspired young artists and consequently dominated 1930’s WPA artwork. While the government instructed the artists they funded to raise the nation’s spirits through optimistic images of technological advances and perseverance, local artists often chose to focus their work on the lives of everyday Americans. Although there were clashes between the artists and their new patron—the government—a common compromise between propagandist governmental approval and idiosyncratic artistic integrity lay in the virtuous simplicity of common people, a celebration of hard work and dismissal of excess. Many of these artists endeavored “to elevate the ordinary and give it new meaning” (Park and Markowitz 1984:139).

This emphasis on the integrity of labor and laborers indirectly reified the artistic process. Artists received a weekly wage for work they produced for the government. This accountability transformed the artistic endeavor from what had been seen as an "expendable leisure-time activity” to a viable form of work (Pohl 2002:366). A multi-layered message of New Deal optimism was deeply imbedded in WPA art. The artists produced work and received compensation, like all other laborers. They celebrated the common laborer in their artwork. Furthermore, these images were showcased in the most ubiquitous forum of the time—the 1,100 new post offices across the nation (Park and Markowitz 1984:4). The government’s buoyant message was clear: hard work by each and every citizen would lead America back to prosperity.

The art styles and themes of Social Realism, Regionalism, and Historicism pervaded 1930’s WPA/FAP art. Social Realism often celebrated industrial workers as the heart of the nation, suggesting that America’s economic viability—its industrial might—rested on the broad shoulders of these rugged individuals. Artistic renderings depicting the strength of laborers also reflected the might of the labor movement during the 1930s (Pohl 2002:373-74). The power of unionized labor was formidable. In fact, in 1935 alone, nearly a third of all U.S. union-affiliated workers were involved in some sort of strike (Park and Markowitz 1984:4). Regionalism enabled local communities to maintain integrity and continuity in the face of the widespread federal relief action that was entirely centralized in Washington, D.C. Artwork celebrating the small-town farmer and other local entrepreneurs allowed for local pride and regional distinction under the auspices of federally mandated aid. Regionalism also served the government’s goal of promoting optimism and unity in times of economic hardship. The singular yet universalistic images of the farmer, the factory worker, etc. managed to bond fragmented communities and promote a common culture and history (Park and Markowitz 1984:3-9). Nonetheless, Historicism resulted in a careful retelling of the past that avoided contentious or divisive issues. WPA murals frequently kept the races separate and diminished women into subservient roles, negating the gains of women and ethnic minorities during the 1920s. Although much of the WPA’s art fell under the thematic rubrics of Social Realism, Regionalism, and Historicism, individual artistic agency and integrity often resulted in significant variation and multivalent symbolism.

SDSU WPA-Era Murals

In August of 2004, routine maintenance and replacement of ceiling tiles in San Diego State University’s Hardy Memorial Tower was interrupted by an unexpected find. During the removal of some ceiling tiles, workmen exposed partial remains of two WPA-era murals on the walls above the bottom floor of Hardy Memorial Tower, which was the school’s original library. Thought to have been entirely destroyed during building renovations in the late 1950s, the murals were hidden above the lowered ceiling-tile horizon on the wall adjacent to Hardy Memorial Tower offices 39, 41, 43, and 44, and across from offices 38 and 40. Most of the upper portions of the murals are present, but the bottom portions have been obliterated. Some of the upper portions have been chipped away as well, exposing plaster, wire mesh, and board-formed concrete walls. Conduit, electrical wires, and outlets are also attached in multiple places to the walls with the extant mural remnants, along with various sheet rock and plywood coverings. One of the two remaining murals faces west; the other faces north. Completion of the tile replacement in late August of 2004 resulted in the images again being sealed by the lowered ceiling and completely hidden from view.

SDSU’s University Archives has partial photographs of the two recently discovered murals. Edward Hess and Gordon Samples took several photographs of the building’s artwork before the 1957-59 renovations. Hess and Samples also photographed three other murals that were likely in very close proximity to the two that were recently uncovered at Hardy Memorial Tower. A cursory investigation of the nearby hallways produced no evidence of these other three murals, implying that they did not survive the building renovations. Nevertheless, further and more detailed searches for these additional historic murals are warranted.

Mural #1: NRA Packages

Figure 2.2 Photograph of Genevieve Burgeson Bredo’s

1936 mural, NRA Packages, uncovered during the 2004 ceiling-tile renovations.

Courtesy of Seth Mallios;

photo edited by Donna Byczkiewicz.

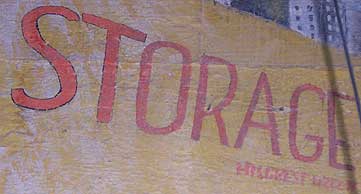

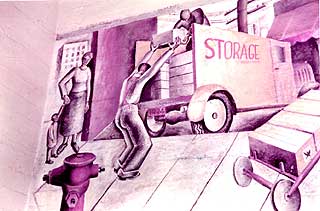

The more intact of the two murals is Genevieve Burgeson Bredo’s 1936 NRA Packages (Figure 2.2). It depicts three men unloading crates from a vehicle and carrying them to a corner store as a woman and child watch. The crates have the National Recovery Act emblem on their sides, a splayed blue eagle with the red letters “NRA” above (Figure 2.3). The vehicle is a yellow moving truck that reads “STORAGE” in large letters above “HILCREST 0212W” in smaller letters (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.3 Close-up photograph of National Recovery Act emblem. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

Figure 2.4 Close-up photograph of moving van inscription. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

The scene is in an urban setting, with high-rise multi-story buildings

and a telephone pole in the background. It likely depicts an area of San

Diego near Hillcrest, which is just north of the downtown area. The vehicle’s

license plate is “1934,” likely a visual pun on the part of

the artist to signify that the mural was being sketched in the year 1934

(Figure 2.5). There is no writing on the red store awning.

Figure 2.5 Close-up photograph of moving van license plate. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

Social Realism permeates the mural. The men are engaged

in the hard work of everyday life as they unload the crates. Their large

hands, elongated arms, and powerful legs accentuate the laborious nature

of their actions. Even the limbs of the mother and child appear exaggerated

in the way she pulls her child’s arm upward. Like many WPA murals,

the sexes are depicted in separate realms; the men work and the women

and children watch. The NRA insignia was also a powerful symbol for the

working class in Social Realism art. Although not clearly designated on

the existing mural, the words “We Do Our Part” often accompanied

the emblem. The National Recovery Act created codes of fair competition

for business, established rules to prevent worker exploitation, and sought

to eliminate child labor. Since the government encouraged people to take

their business to stores that participated in this worker-friendly program,

producers and shop owners often displayed the NRA emblem on their goods

and storefronts.

Figure 2.6 Howard Hess and Gordon Samples’ ca. 1959 photograph of Bredo’s NRA Packages mural. Courtesy of the San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

The SDSU University Archives contain a photograph that captures most of Bredo’s NRA Packages mural (Figure 2.6). Taken by Howard Hess and Gordon Samples in ca. 1959, the photograph is truncated on the right side and omits approximately one-third of the mural. It does not include the third man with the cart of boxes or the right half of the storefront. It does, however, contain parts of the mural that were destroyed, including a fire hydrant in the lower left corner, the first man’s rolled up pant cuffs, and the bottom half of the moving cart.

Mural #2: San Diego’s Industry

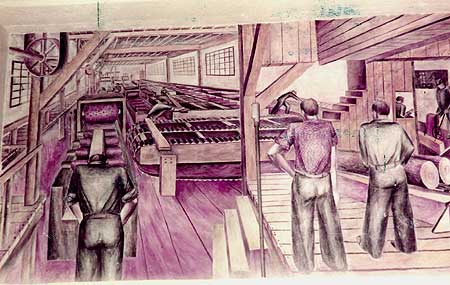

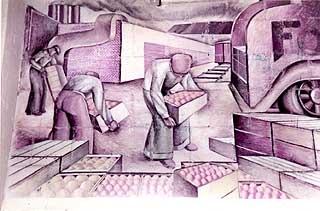

George Sorenson’s 1936 San Diego Industry depicts sequential stages in the local fish industry, including procurement, processing, and distribution (Figure 2.7a-c).

Figure 2.7 Photograph of George Sorenson’s

1936 mural, San Diego Industry, uncovered during the 2004 ceiling-tile

renovations. (A) is the left segment, (B) is the middle segment, and

(C) is the right segment.Courtesy of Seth Mallios; photos edited by

Donna Byczkiewicz.

It runs from left to right. The extant portions of the mural contain about twenty people, although it is likely that the original artwork in its entirety contained many more individuals. The extreme left edge of the mural, which was largely destroyed, shows a man with a large rimmed hat who is fishing with a bamboo pole in his left hand (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 Close-up photograph of first fisherman. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

To the right of him stands a bald man with spectacles who weighs many

large fish on a scale (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9 Close-up photograph of fish weigher. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

A man wearing a beret is holding one of these fish, about to place it

on the scale (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10 Close-up photograph of fisherman

with beret. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

A spit of land, harbor, dock, and flat fishing vessel are in the background,

just behind the man with the beret. This part of the scene likely depicts

San Diego harbor. Immediately to the right is a chute loaded with fish,

one of which has already been beheaded (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11 Close-up photograph of fish chute. Courtesy

of Seth Mallios.

At least two men are standing on opposite sides of the table that catches the fish for cleaning. Very little of the mural is intact for the next five feet to the right. Although a faint hand sketching of the mural is evident, nearly all of the painted detail is gone. There is a small, fully painted section that shows part of a person’s arm holding a gutted fish. The next extant portion depicts nearly a dozen women standing in two sets of assembly lines, one in the foreground and one in the background (Figure 2.12).

Figure

2.12 Close-up photograph of assembly-line women. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

Although the eye-level perspective of the mural at this

point hides the identity of what is being processed, the adjacent section

to the right takes a bird’s-eye view, revealing the open cans of

fish which the women have produced. Large canning machinery is in the

background to the right of the assembly line. There is also a man working

the many conveyor belts that are lined with short cylindrical cans (Figure

2.13).

Figure 2.13 Close-up photograph of man working the conveyor belts. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

At the far right of the mural, there are three Asian men standing behind

large bins of canned fish (Figure 2.14). In the background behind them,

a fourth man pushes an additional bin away from an open storage area that

contains many unmarked boxes.

Figure 2.14 Close-up photograph of three Asian men. Courtesy of Seth Mallios.

While Sorenson’s San Diego Industry addresses aforementioned issues

of Social Realism in its depiction of the working class as essential cogs

in the American industrial machine, it exemplifies Regionalization. Regionalized

WPA murals simultaneously accomplished two disparate goals. First, they

followed the federal standards of presenting optimistic portraits of workers

laboriously restoring the promise of the nation. Second, they highlighted

the industry that was particular to their locale. WPA murals that successfully

showcased regional specifics included Detroit, Michigan’s Automobile

Industry, Canton, Ohio’s Steel Industry, Benton, Arkansas’

The Bauxite Mines, and Kilgore, Texas’s Drilling for Oil. For San

Diego, the business of fishing was a primary industrial signature of the

time.

Sorenson’s mural was more progressive and less typical of WPA art

than Bredo’s work in terms of its treatment of women and ethnic

minorities. Although both murals separate men from women, Sorenson placed

the women as an active component of San Diego industry. His female workers

are far from passive onlookers; they are an essential part of the industrial

process. In addition, Sorenson incorporates different ethnicities into

his images. The man on the dock holding the fish is likely African-American,

and he does not appear to be segregated from other ethnicities in the

workplace. The same cannot be said for the three Asian men at the end

of the fish-processing procedure. They are clustered off to the side,

portrayed in distinct clothing, and the slant of their eyes is pronounced,

likely to emphasize their ethnic difference.

Figure 2.15 Howard Hess and Gordon Samples’ ca. 1959 photograph of Sorenson’s San Diego Industry mural. Courtesy of the San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Hess and Samples photographed a small section of Sorenson’s mural

in ca. 1959 (Figure 2.15). Their image recorded the mural from the bamboo

pole of the fisherman on the left to the industrial chute on the right.

It focused primarily on the two men who loaded and weighed fish on the

dock. The photograph did not include any of the assembly-line women, canning

machinery, or Asian packers.

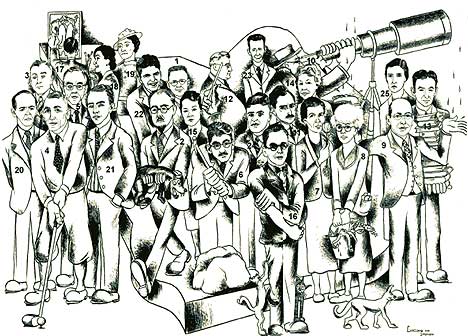

Sorenson’s WPA-era mural was not his only artwork that left a permanent

mark on San Diego State College. He and Don Luscomb also drew eight large-scale

illustrations for the 1936 San Diego State College yearbook, Del Sudoeste.

One of their drawings included a detailed group caricature of the faculty

(Figure 2.16).

Figure 2.16 Don Luscomb and George Sorenson’s

yearbook caricature of the San Diego State College faculty in the 1936

Del Sudoeste. Courtesy of the San Diego State University Library, University

Archives, Photograph Collection; Donated by the Don Luscomb family. The

faculty are as follows: 1) Arthur G. Peterson, Economics; 2) Franklin

Walker, English; 3) Charles E. Peterson, Physical Education; 4) Oscar

Baird, Physics; 5) George Livingston, Mathematics; 6) Baylor Brooks, Geology;

7) Dorothy Harvey, Botany; 8) Myrtle Johnson, Zoology; 9) Dean Blake,

Meteorology; 10) Alvena Storm, Geography; 11) Leslie Brown, French and

Spanish; 12) Charles Leonard, History; 13) John Paul Stone, Library Instruction;

14) W. T. Skilling, Astronomy; 15) Mary McMullen, Educational Guidance;

16) Robert Harwood, Zoology; 17) Everett Gee Jackson, Art; 18) Marjorie

Borsum, Art; 19) Lena Patterson, Art; 20) Elmer Messner, Chemistry; 21)

Chesney Moe, Physics; 22) Leo Calland, Physical Education; 23) Dudley

Robinson, Chemistry; 24) Fred Beidleman, Music; and 25) Marguerite Johnson,

Latin.

Photographs of Three Other Hardy Memorial Tower Murals

SDSU’s University Archives also contains photographs of three other WPA-era murals once displayed in Hardy Memorial Tower. Each of these murals embodies the themes of Social Realism and Regionalization, depicting working-class labor in the local San Diego industries of lumber, orange production, and military service. The original murals were likely in close proximity to the two recently rediscovered murals and are thought to have been destroyed during pre-1960 building renovations. Hess and Samples took each snapshot in ca. 1959.

The first photograph of these additional murals is of Genevieve Burgeson Bredo’s 1936 Lumber Working (Figure 2.17).

Figure 2.17 Howard Hess and Gordon Samples’ ca. 1959 photograph of Bredo’s 1936 Lumber Working

mural. Courtesy of the San Diego State University Library, University

Archives, Photograph Collection.

It, like Sorenson’s fish mural, showcases the means of production—the

instruments and subjects of labor—that are inherent to the local

economy. Hess and Samples’ other photographs recorded the works

of Ellamarie Packard Woolley, a San Diego native, San Diego State art

student, and daughter of Phineas Packard, the founder of San Diego’s

Arts and Crafts Press. Woolley’s two 1936 Hardy Memorial Tower murals

are entitled Packing Oranges and Sailors Going to Hell. Packing Oranges

bears a striking resemblance to Bredo’s NRA Packages, as each contains

three broad-shouldered male workers in an urban setting, unloading goods

from a truck (Figure 2.18).

Figure 2.18 Howard Hess and Gordon Samples’ ca. 1959 photograph of Woolley’s 1936 Packing Oranges mural. Courtesy of the San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Sailors Going to Hell is distinctive in its ominous imagery (Figure 2.19). For example, the ship’s far left cannon points directly at the downtrodden sailors as they board the vessel. Building on the maxim that war is hell, the mural’s ambiguous title hints that the ship is either headed to hell or the vessel itself is a hell on earth. Overall, these three additional murals further demonstrate how local artists at times addressed, embraced, and challenged the federal government’s guidelines for WPA/FAP artwork.

Figure 2.19 Howard Hess and George Samples’ ca.

1959 photograph of Woolley’s 1936 Sailors Going to Hell mural. Courtesy

of the San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph

Collection.

Conclusion

Much of San Diego State College was built by workers employed by WPA Projects

when it was moved to Montezuma Mesa in the 1930s. Contemporary murals

at Hardy Memorial Tower showcased the enduring spirit of these and other

laborers who toiled in local San Diego industries. This artwork both celebrated

and exemplified the spirit of the New Deal, illustrating the ability of

ordinary workers to help resuscitate the nation.

Ever since its Depression-Era construction, San Diego State has been the

people’s college of San Diego. Today, one in every seven adults

in San Diego who holds a college degree attended SDSU. Although the landscape

of the university continues to expand and change, remnants of San Diego

State’s humble origins lay at its core. Even when the past was thought

to have been destroyed, as in the case of the two recently discovered

WPA-era murals in Hardy Memorial Tower, the soul of the university emerges

in the most unexpected places and displays the legacy of its hard-working

laborers, the common people of San Diego.

References Cited

Bourne, Francis T.

1946 Preliminary Checklists of the Central Correspondence Files of the

Works Projects Administration and Its Predecessors, 1933-1944. Records

of the Works Project Administration, Record Group 69, National Archives,

Washington, D.C.

Branton, Pamela Hart

1991 The Works Progress Administration in San Diego County, 1935-1943.

Unpublished M.A. thesis, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA.

Burner, David

1979 Herbert Hoover: A Public Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hardy, E. L.

February 23, 1933 The College and the Depression. Transcript, “Radio

Talk” 9:10pm.

McKinzie, Richard D.

1973 The New Deal for Artists. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University

Press.

Morgan, Ted

1985 FDR: A Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Park, Marlene, and Gerald E. Markowitz

1984 Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal. Philadelphia,

PA: Temple University Press.

Pohl, Frances K.

2002 Framing America: A Social History of American Art. New York: Thames

and Hudson.

San Diego Union

1935 “1,240,000 WPA Aid,” 1 October: sec. 1, 2.

Webbink, Paul

1960 Unemployment in the United States, 1930-1940. In The Great Depression,

Ed. David A. Shannon. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, pp. 6-7.