Home

Mission Statement

Editorial Policy

Submission Information

Volume One

Casual Papers

Fort Guijarros

Volume Two

Archaeology Field Report on the Search for Fort Guijarros

Ronald V. May

Background Historical Research

Between 1981 and 1995, the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation conducted

archaeological investigations to define the physical appearance of Fort

Guijarros, the 1796 Spanish cannon battery on Ballast Point, San Diego,

California (May 1995:4-15; May 1996:1-18). Historical research on the

location of Fort Guijarros began in 1980 (Colston 1982:61-83) and continued

through 1989 (Cutter 1989:6). Archival records from the United States,

Spain, and Mexico revealed 18th-century Spanish authorities had selected

Punta de los Guijarros as the site for a defensive cannon battery.

Although no Spanish or Mexican maps have been found to depict the shape

of Fort Guijarros, United States government maps provided strong clues

to aid archaeological test excavations. In the eighteenth Century, San

Diego provided Spain with one of the best harbors to stage religious and

secular control of California (Figure 8.1).

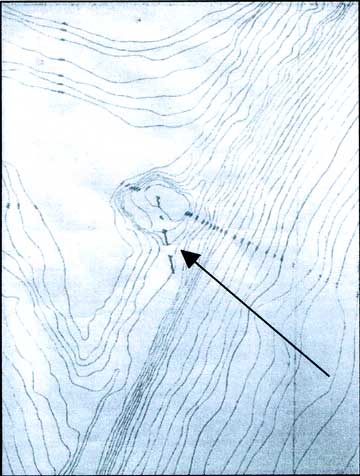

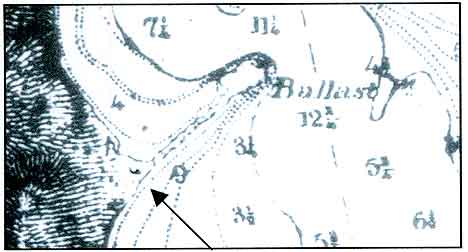

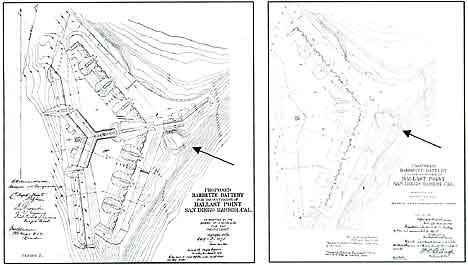

Figure 8.1 The earliest known American topographic survey of Ballast Point

showing the location of the ruined fort, 1867. Arrow points to mound of

Fort Guijarros’ ruins, with notation “Ruins of Spanish Battery.”

Map of Ballast Point, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The entrance to San Diego Bay is constricted by a narrow spit, marked

on Spanish maps as “Punta de los Guijarros” and United States

maps as “Ballast Point” (Figure 8.2).

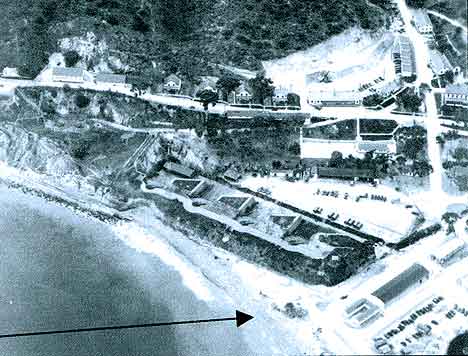

Figure 8.2 Ballast Point, Point Loma. Aerial view taken between 1922-1935, showing U.S. Army Fort Rosecrans. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Collection, P:04-7091.

West of Ballast Point is a 350-foot-high uplifted marine sandstone hill known today as Point Loma. East of the harbor entrance was a nearly level marshland identified on modern maps as North Island (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Aerial photograph of Point Loma looking

north towards San Diego. North Island is located in the upper right of

the picture across the harbor. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Collection,

90-467.

Ships sailed past Ballast Point one mile north to the Embarcadero to anchor

and conduct business. Spanish law required foreign ship masters to register

with the commandante of the Royal Presidio de San Diego, some four miles

north of the Embarcadero. Those traveling to the Presidio passed overland

through the marsh and the San Diego River to a hill site overlooking San

Diego Bay to the south and the San Diego River and Mission Valley to the

north.

Spanish military rule in San Diego centered at the Presidio. The commandante

assigned garrisons of soldiers to Mission San Diego de Alcalá,

Fort Guijarros, and to patrol the El Camino Real (King’s Highway).

Approximately one mile east of the Presidio, Mission San Diego de Alcalá

had been attacked and burned in 1774 by Native Americans and rebuilt as

an adobe fortification garrisoned by soldiers. Troops also patrolled agricultural

operations in inland valleys for the mission. Within this context of rotating

troops, Fort Guijarros served Spain as an outpost on Ballast Point.

Challenges to the Spanish claim to California and the Pacific coast came

in 1789 when Spanish ships and a shore battery captured several English

war ships at Nootka, British Columbia (Cook 1973:344-345; Floyd 1995:17).

This incident nearly triggered war between England and Spain, which resulted

in the 1790 Nootka Convention. This treaty prohibited English contact

with California south of Sonoma.

The Viceroy of New Spain, Conde de Revillagigedo, ordered a policy of

defensive possession in California to enforce the articles of the Nootka

Convention (Chapman 1921-515-516). California Governor Jose Joaquin de

Arrillaga carried out that policy in 1792 by ordering studies and selection

of sites for military fortifications at the harbors of San Francisco,

Monterey, Santa Barbara, and San Diego. Juan Francisco de la Bodega indicated

one potential fortification site on the map of San Diego Bay and surrounding

landforms that same year, but the selection of Ballast Point occurred

several years later.

The Spanish frigate Princessa shipped wood from Monterey to San Diego

in 1793 for the eventual construction of a barracks and battery at the

Presidio (Figure 8.4).

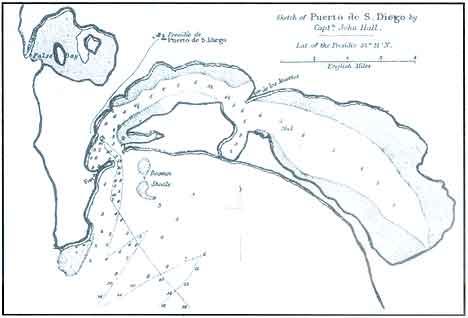

Figure 8.4 1839 map by English Captain John Hall showing San Diego and the location of the Fort and Presidio de Puerto de San Diego as well as navigation information such as channel depth. In Richard F. Pourade’s The History of San Diego: The Silver Dons.

Miguel Costansó selected Ballast Point that same year for the

San Diego battery (Colston 1982:62). Following the change of command from

Arrillaga to Governor Diego Borica in 1793, Spanish authorities shipped

1410 wood planks, 50 beams for the esplanade, 6 beams for the barracks,

100 boards and 300 stones to San Diego.

A work force of native Kumeyaay Indians and Spanish Catalonian volunteers

drafted from a construction project at the Royal Presidio were shipped

by flatboat five miles south to construct the battery at Ballast Point.

During construction in 1795, a temporary wicker-work battery filled with

sand defended the bay. Construction crews demolished the beach battery

upon completion of Fort Guijarros in 1796.

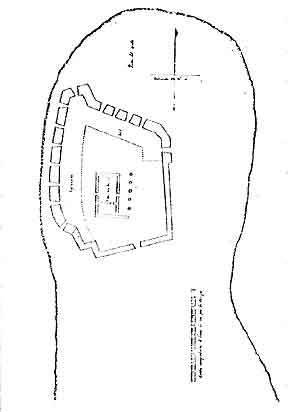

Figure 8.5 Spanish cannon battery in San Francisco,

California at the mouth of the harbor.

Alberto de Córdoba, “Plano de la Bateria…de San Joaquin…de

San Francisco, July 20, 1796 Ramo de Provincias Internas, b.216,ff236-7.”

Although neither records nor drawings are known to exist for San Diego’s

battery, plans do exist for one in San Francisco (Figure

8.5). Two years prior to construction of Fort Guijarros, Cordoba

documented the San Francisco battery with fourteen cannon ports between

20-foot-thick merlones in an as-built map (Colston 1982:66). This design

showed the San Francisco battery to have 40-foot-wide walls topped on

the exterior half by the merlones. The gunports measured 2.5 feet wide

at the interior face and flared to 10 feet at the exterior. The interior

face of the merlones measured 8 feet high and sloped toward the exterior

to 4 feet. Destroyed by an earthquake in 1815, Cordoba’s battery

was replaced by a horseshoe-shaped battery in 1816 (Bancroft 1886:651).

Analysis of instructions provided by Don Pedro de Lucuze against plans

for coastal cannon batteries constructed in Campeche, Mexico, provided

further evidence for the appearance of California Spanish cannon batteries

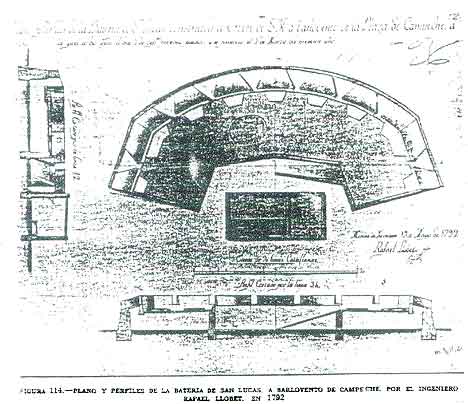

(May 1995:7). Joaquin Antonio Calderon Quijano published the designs of

18th-century Spanish engineer Rafael Llobet to defend Campeche from English

and privateer assaults.

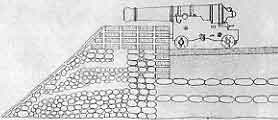

The plans of Bateria de San Lucas closely resemble a mark on the 1851

United States Coast Survey map of Ballast Point (May 1995:9). Llobet followed

instructions detailed in 1772 by de Lucuze, but expanded the esplanade

to roughly 40 feet. Elevated 28 feet above the natural ground, Batería

de San Lucas protected an interior barracks (Figure

8.6).

Figure 8.6 Fort analogy from Joaquin Antonio Calderon Quijano showing cannon battery in Campeche, Mexico. Fort Guijarros may have had a similar appearance in 1800.

The building material available for most Spanish fortification construction

in New Spain consisted of quarried hard stone, such as granite or chalkstone.

Both the interior and exterior faces of Batería de San Lucas are

vertical in the 1792 plans. De Lucuze illustrated a hard stone vertical

exterior or battery face, but both vertical and ramped interior faces

were made (Quillin and Quillin 1988:3-7; May 1995:6). Quarry stone is

not available on the San Diego coast of California and Spanish architects

were forced to use soft marine sandstone, mud and cobblestones on Ballast

Point. The lowest layer of architecture includes crudely-shaped blocks

of marine sandstone.

Fort Guijarros served the Spanish government as an outpost garrisoned

by troops from the Presidio and their families until the Mexican government

assumed command of San Diego in 1822. Although no foreign navy invaded

California, Spanish soldiers engaged in combat with sailors of the American

merchant brig Lelia Byrd in 1803 (Colston 1982). Mexican soldiers also

exchanged cannon fire with sailors of the American sailing ship Franklin

in 1828. Following demilitarization of San Diego in 1835, the garrison

at Fort Guijarros closed down and stripped the barracks, casemate, and

walls. Cannon, powder, and shot were left on the walls to salute incoming

shipping as late as 1843 (Sandels 1945) (Figure

8.7).

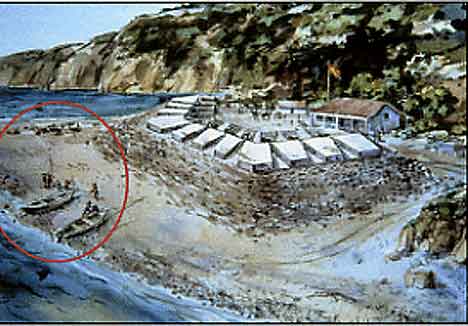

Figure 8.7 An 1843 sketch by Swedish tourist G. M.

Waseurtz af Sandels of La Playa with Fort Guijarros depicted to the far

right. G. M. Waseurtz af Sandels, 1945 A Soujourn in California by the

King’s Orphan: the Travels and Sketches of G. M. Waseurtz af Sandels,

a Swedish Gentleman Who Visited California in 1842-1843. San Francisco:

Grabhorn Press.

Lacking a maintenance program, Fort Guijarros fell prey to construction

salvage and vandalism. Severe winter storms eroded and stripped the beach

back ever further north, causing Spanish architecture to crumble into

the sea. Recent analysis of shore lines marked on the 1851 U.S. Coast

Survey map of San Diego, the 1867 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map of

Ballast Point (See figure

8.1), and photographs taken after 1900 demonstrated that the

erosion stripped away as much as a third of Fort Guijarros (Donaldson,

personal communication 1996).

The remaining portions of the ruins of Fort Guijarros were damaged by

tile salvagers through the end of the 19th century. Construction of the

1853 Point Loma Light House by the U.S. Light House Service included Spanish

tiles mined from Fort Guijarros and used in the tower. These tiles were

exposed during 1983 restoration work and confirmed by Ronald V. May. Civilian

mariners working to construct shanties and industrial structures for the

whaling companies on Ballast Point between 1858 and 1886 stripped Spanish

tiles to be used for floors and foundations (May 1985a; 1986; 1988).

Eventually, the merlones collapsed in an avalanche of loamy sand mixed

with whitewashed mortar, broken fired tiles, cobblestones, and broken

unfired adobe. High storm surf washed and scoured the rubble, melting

that soft adobe and depositing seaweed and flotsam among the heavier cobbles

and tile.

Legal battles between the City of San Diego and U.S. Army between 1850

and 1870 over the title to Point Loma and Ballast Point rendered the area

a no man’s land until a federal court decided in favor of the Department

of War (May 1985b:121-136). During the 1850s, City Trustees auctioned

off Ballast Point to Mexican War veterans who lobbied Congress to develop

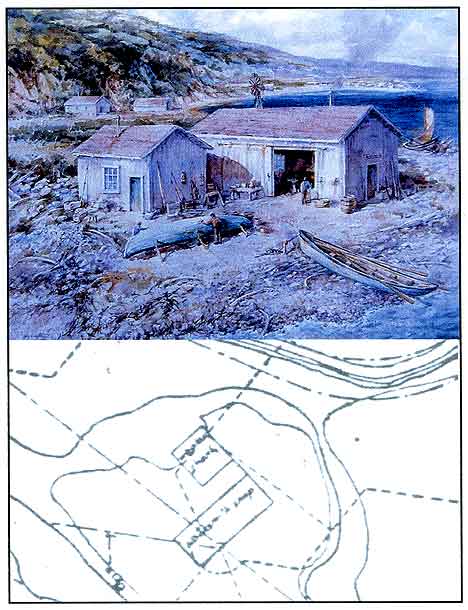

a military post on Point Loma (Figure 8.8).

Figure 8.8 1852 U.S. Coast Survey Map view of entrance to San Diego Bay, as part of general sailing instructions from San Diego to San Francisco, with Point Loma rising to the left. Reconnaissance under the command of Lt. James Alden, U.S.N. Assistant.

The $20-an-acre investment would have paid $100,000, had the federal

court not invalidated the City of San Diego’s title

(Figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9 1857 Map of San Diego showing location of Fort Guijarros. Set 10, No. 35 by Linden Lohe.

The retired soldiers then leased Ballast Point to civilian shore whaling

companies sometime between 1858 and 1860 (May 1985a; 1986). Taking advantage

of the relatively level surface of the 20-foot-high and 40-foot-thick

north wing of Fort Guijarros, Packard Whaling Company owners erected a

small shanty house and a larger blacksmith shop

(Figure 8.10). Later joined by the Johnson Company, the Packard

Company erected shanties, warehouses, and at least one tryworks oven along

the spit at Ballast Point to conduct whale oil rendering operations. Tiles

removed from the Fort Guijarros ruins were stacked into the foundation

of the tryworks oven further east on Ballast Point. Large sandstone blocks

used to build the blacksmith shop forge may have been salvaged from the

interior of Fort Guijarros (May 1994;1996:10-13).

Figure 8.10 Top: Jay Wegter’s watercolor interpretation of the pre-1896 whaler’s shanty and blacksmith’s shop. Bottom: 1896 Army Corps of Engineer’s Map excerpt showing the mound of the ruins of Fort Guijarros with the whaler’s shanty and blacksmith’s shop buildings located on top of the mound.

Following the 1870 federal court decision in favor of the U.S. Department

of War, civilian title extinguished and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

assigned Lt. John Hall Weeden to inspect Point Loma in 1872 and evict

the “squatters.” Bowing to popular local support for continuation

of the whaling operation, Lt. Weeden allowed the whalers to continue until

1873 and a number of elaborate battery designs were completed for a new

“Fort San Diego” (May 1985b:121-136).

Lt. Weeden evicted the whalers at the end of the 1873 season and commenced

construction of an immense artillery battery, just west and north of the

Fort Guijarros ruins. Analysis of the 1851, 1867, and later U.S. Army

maps has revealed a difference in 11 feet between elevations (Buchanan

1996). Although no record of demolition of Fort Guijarros has surfaced

in research of the U.S. National Archives, Lt. Weeden’s construction

work at Fort San Diego would account for the elevation differential

(Figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 Two maps for Fort San Diego, the proposed

elaborate Barbette Battery at Ballast Point, in (left) 1872 and (right)

1873. Both of these proposals were designed around the ruins of Fort Guijarros,

taking advantage of the same cannon firing lines used by the Spanish engineers

when they designed Fort Guijarros to protect the entrance to San Diego

Bay.

The merlones were not present in the archaeological excavations, except

as rubble fill down the Spanish cobblestone buttress, suggesting demolition

and removal to an unknown location. Congress terminated funding for Lt.

Weeden’s Fort San Diego in 1874 and the elaborate designs were never

completed, leaving behind only the documentary record and earthen mound

as a reminder of that episode of San Diego’s coastal defense. Soon

afterwards, the U.S. military presence temporarily departed Ballast Point.

The 1896 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map documented the site of a Whaler’s

Shanty and Blacksmith Shop on top of the ruins, indicating the shore whaling

companies returned to Ballast Point following Lt. Weeden’s departure (See

figure 8.10). The 1896 survey map formed the basis for elaborate

designs of a U.S. Army post for San Diego. In 1898, civilian construction

crews erected a large artillery battery, Battery Wilkeson, on the earthen

foundations of the unbuilt Fort San Diego under the supervision of the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (May 1985c).

Excavated 30 to 40 feet behind the ruins of Fort Guijarros, Battery Wilkeson

consists of cast concrete and volcanic boulder walls in excess of 32 feet

thick (Figure 8.12). Designed to withstand

incoming battleship artillery shell, Battery Wilkeson had been excavated

deeper than the 1796 Spanish landform. Earth from the 1898 excavation

covered the Ballast Point beach and ruins of Fort Guijarros to obscure

the former mound and courtyard behind the walls. As Fort Rosecrans continued

to develop through the early 20th century, more fill covered the area.

By the time the U.S. Army decommissioned Fort Rosecrans in 1959, and the

land transferred to the U.S. Navy in 1962, Fort Guijarros had been completely

covered with fill. Automobiles had parked over the surface through the

following decades, until Building 539 had been erected for a U.S. Department

of Defense research facility in 1975. Building 539 transformed into the

U.S. Navy Fire Station in 1989, which continues to operate on the site

into the present.

Figure 8.12 Circa 1943 aerial view looking west towards United States Army Fort Rosecrans showing Coast Artillery Battery Wilkeson, which was built in 1898. Fort Guijarros is located beneath the sand in the foreground (see arrow). Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:04-7086.

Archaeological Investigations

The United States Navy Submarine Base invited civilian historians to conduct archaeological investigations in search of Fort Guijarros in 1980 (May 1982). The Navy issued an American Antiquities Act Permit to Ronald V. May in 1981 and investigations commenced to search for remains of the walls of Fort Guijarros. By 1982, the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation incorporated with non-profit status and applied for subsequent archaeological permits.

The primary objective for all the investigations has been to obtain evidence for the physical appearance of Fort Guijarros. Secondary research designed methods to analyze quantities of food bone and other kitchen debris to characterize the quality of life Spanish soldiers experienced during the occupation of 1796-1822 and Mexican military occupation of 1822-1835. Work on Fort Guijarros’ walls occurred in 1981-1982, 1985, 1987, and 1989-1995. The search for residential areas occurred in 1983, 1984, and 1986. Other investigations, involved shore whaling sites elsewhere on Ballast Point, occurred in 1988-1989 and 1991-1992.

In theory, the boundaries of Fort Guijarros should include the walls and

associated living areas within the site. This would include the soldiers’

barracks, powder house and storerooms, kitchen, corrals, and refuse areas.

A hypothetical boundary has been marked to record the archaeological site,

CA-SDI-12,000, with the California Site Survey.

Fort Guijarros spans over 200 feet in several directions. Buried under

the earth buttress south of Battery Wilkeson and extending to the cobblestone

shoreline of Ballast Point, the ruins of Fort Guijarros also extend east

to the foot of Rosecrans Street. This immense area posed problems for

meaningful archaeological inquiry.

The overall strategy involved the placement of large excavation blocks

between existing buildings, parking lots, paved roads, and at the edge

of the 1898 fill slope of Battery Wilkeson. In total, eight blocks of

varying dimensions were excavated between 1981 and 1995.

Investigations of U.S. National Archives maps of Point Loma, Ballast Point,

and former U.S. Light House and U.S. Army Fort Rosecrans activities provided

evidence that the ruins of Fort Guijarros were buried by substantial earth

fill between 1867 and 1945. The current paved asphalt parking, asphalt

road, and south end of Rosecrans Street are artificially elevated as much

as 9.84 feet above the original 1796 beach (Figure

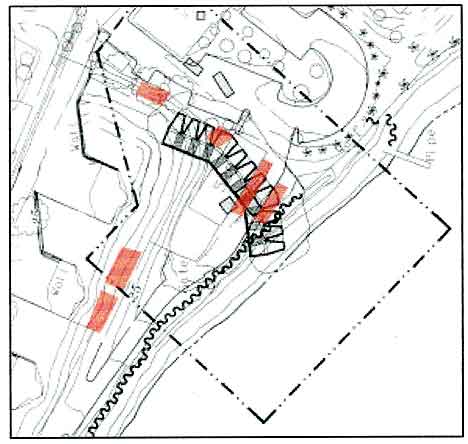

8.13).

Figure 8.13 Overlay of excavation fields (red) upon composite map of proposed site boundary as theorized by Architect Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA. The excavation targeted the fort walls as well as areas in front of and behind the defense walls.

Test units in 1981 revealed a deeply stratified earth fill. The 1945 fill

ranged from 1.64 to 4.92 feet thick. Several strata appeared to have been

loads of yellow, orange, and tan sands dumped in a pile. A dark black

to brown burned strata rich in U.S. Army artifacts dating from 1890 to

1924 extended throughout the area. Thick beach sand layers separated the

U.S. Army strata from a dense dark brown indurated sand filled with civilian

artifacts that dated from 1850 to 1886. This included whalebones from

the shore whaling operation.

Excavation of the U.S. Army and civilian shore whaling fill deposits posed

significant challenges and considerations for the Navy and Fort Guijarros

Museum Foundation. These included logistics and safety considerations,

collections management, scheduling, leadership and staffing sources, and

the research value of the project results. These challenges included:

1. Scientific Value. The 1.64 to 4.92-foot-thick post-1835 fill is comprised

of dozens of strata ranging from 4 inches to nearly 3.28 feet. High concentrations

of artifacts including burned architecture and trash pits deposited by

U.S. Army and American civilian shore whaling behavioral activities added

archaeological value to the fill. Excavation design would have to treat

these strata with a respect equal to that given to the Spanish ruins below.

2. Safety. California and federal Occupational Safety Hazards Act regulations

require safety shoring of all excavations below a depth of 4 feet. The

Navy required massive wooden shoring for the 1983, 1984, 1986, and 1989-1995

excavations to protect the excavation crew. Each time the archaeological

excavation attained a depth of 4 feet, heavy wooden shoring was installed

under the supervision of a civil engineer. The Base Civil Engineer reviewed

and approved shoring in all instances. The SUBASE installed shoring in

1988, to protect the adjacent fire station from structural damage. In

several instances, the shoring remained in place during backfilling to

ensure public safety.

3. Logistics. Long-term scientific investigation through complex U.S.

Army, American shore whaling, and Spanish/Mexican rubble strata required

commitment of substantial funds, acquisition of equipment, and sources

of funding for the labor and materials to clean, catalog, analyze, conserve,

and package the artifacts into environmentally stable containers (Figure

8.14).

Figure 8.14 Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation laboratory in Building 127, Fort Rosecrans Historic District, Naval Base Point Loma. Featured in the photo are Dale Ballou May at the computer, Ron May near the door, Susan Floyd to his left, Heather Haisten to his right, and G. Scott Anderson at the bottom of the photo.

4. U.S. Navy Schedule. The U.S. Navy had little experience with long-term

archaeological research programs. Volunteer archaeological projects led

by skilled archaeologists required weekend scheduling and patience on

the part of the U.S. Navy, which required annual permits with results

at the end of each year.

5. Collections Management Resources. The scientifically important strata

and trash pit features that covered Fort Guijarros contained thousands

of artifacts, including corroded metal, fragile fiber and textile, food

bone and marine shell, brittle leather and wood, and delicate glass and

ceramics. All the artifacts and food remains required special packaging

and conservation in addition to simple field cataloguing and analysis.

Virtually 90% of the collections recovered from Fort Guijarros were within

the U.S. Army and shore whaling deposits.

6. Qualified Leadership. The Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation would have

to provide a qualified historical archaeologist willing to invest many

years of volunteer time to the project.

The Board of Directors of the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation committed

to addressing and solving all of the above problems.

The Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation has co-mingled supplies, equipment,

and resources to the Archaeology Lab operations conducted in Building

127 (Figure

8.14). All Navy computers were replaced by Fort Guijarros property

in 2005. The Foundation funds a part-time contract employee as Laboratory

Supervisor under the supervision of Ronald V. May, Director of Archaeology

Programs. Volunteers work in the field, laboratory, and as tour docents.

The Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation received federal and state non-profit

status in 1982 to support the archaeology programs on the U.S. Navy Submarine

Base, San Diego. Issues of safety, logistics, and scheduling have been

coordinated with SUBASE Civil Engineers and Environmental Officers.

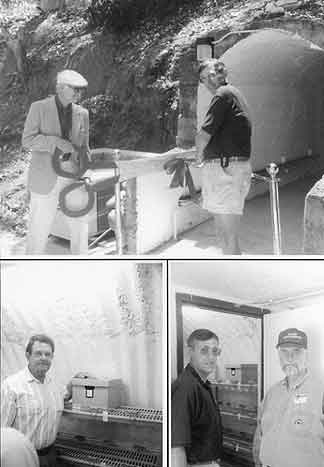

The SUBASE has assigned Building 127 and retrofitted an underground bunker

(Building 257) for temperature and humidity control to conserve the archaeology

collections to the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation (Figure

8.15 and 8.16). This bunker has been named the Ballast Point Repository

and was dedicated on July 15, 1995. Computers, furnishings, and supplies

had been funded by a Department of Defense Legacy Program grant and funds

from the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation. New upgraded computers were

privately funded by founding member Caroline Crosby.

|

Figure 8.15 Ballast Point Repository. |

Figure 8.16 Top: C. Fred Buchanan cutting the dedication ribbon for Captain David Stanley, Commanding Officer, U.S. Naval Submarine Base, San Diego, on July 15, 1995. Lower left: CDR. John C. Hinkle, U.S.N. (ret), former Commanding Officer and foundation co-founder placed the first box in the Ballast Point Repository. Lower right: Captain David Stanley and Ron May, Chair of the Board of Directors of the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation, stand at the entrance of the Ballast Point Repository. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection: P:95-1985; P:95-1988; P:95-1995.

Excavation Strategy

The long-term excavation strategy involved backhoe trenching for architectural

and residential features, followed by field block excavation, and individual

unit excavation within the blocks (Figure 8.17). Since no one knew beforehand if soil color and composition change indicated

architecture, dissolved architecture, fill, ocean erosion, graded cutting,

or just a pile of trash, the field strategy required assigning a “locus”

number for the location of the color and soil composition change. Segregation

of the land by field block, unit, and loci enabled later laboratory analysis

to properly interpret if the colors represented walls, foundations, trenches,

privies, or piles of trash. In this context, the arbitrary term locus

does not conform to other archaeologist’s field terminology.

At the time, it seemed best to simply call all soil color and composition

change a locus and key field notes, recovery bags, and catalogues to those

terms. A Roman numeral was been assigned to each block of field units.

The dimensions of each block varied, depending on physical restrictions

such as Building 539 and paved asphalt streets. Within the block, grids

were measured in metric units.

Figure 8.17 First day of excavation, June 6, 1981. The backhoe trench revealed architectural ruins below the parking lot. Commander John C. Hinkle, Lt. Schnelzer, and Sharon Preston are observing the field crew. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection.

The first field crew included a mix of professional archaeologists and

avocationals who volunteered their time, equipment, and resources to make

this a successful project. A review of the field notes and photo records

revealed partial list of many of the people who participated in the project

that first summer (in random order):

Stanley R. Berryman, Judy Berryman and their son R.J., Jerry Schaefer,

Steve Apple, Rebecca Apple, Jim Royle, Marje Royle, Rick Norwood, Brian

Glenn, Kaja Mitter (Lausten), Susan Walter, Jesús Benayas, Andrew

Pignolio, Steve Van Wormer, Paul Chace, Alan Chace, Richard Gadler, Don

Laylander, Butch Hancock, Ginger Hancock, Judy Swink, Wayne Kenaston,

Dan Brown, Linda Roth, Roxie Phillips, Carolyn May, Joyce Reading, Juan

Bertran, Sally Hyslop, Anna Noah, Florence Sloane, Russell Stewart, Mary

Lou Hewitt, Maria Olson, Quentin Olson, Ron Morgan, Marilyn Morgan, Howard

Schwitkis, Elfie Schwitkis, Julie Iavelli, Gil Boggs, Toy Boggs, Robert

C. Forsythe, Susan Floyd, Mary Tommey, Jerry Hall, Lesley Ragan-Davis,

Joe Young, Everett Papp, Mark Stein, C. Smith, C. Hartley, J. Kordat,

Joe Young, Tod Michael, Pat McCarty, Jerry Hall, A. Pierce, Karen Trexler,

and Cyndi Duff.

Excavation results

The following is a description of the eight blocks excavated between 1981 and 1995.

|

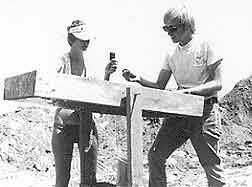

Figure 8.18 Judy Swink (left) and Jim Royle (right) are screening dirt from the first trench and are recovering artifacts for later analysis. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection. |

Field I

The U.S. Navy cut a backhoe trench from Rosecrans Street to the west end

of Building 539 on June 6, 1981 (See Figure 8.17).

The backhoe piled soil in a row south of the trench for the volunteers to

screen (Figure 8.18). Commander John C. Hinkle,

Commanding Officer, U.S. Navy Submarine Support Facility, and his staff

coordinated logistics with archaeologist Ronald V. May as field director.

As the backhoe bucket penetrated a waterline late that morning, Commander

Hinkle had the water shut off. When the water subsided, layers of sand,

charcoal, and broken fired adobe tiles were exposed in the trench sidewall.

The team examined the sidewalls and placed test pits over the wet tiles

and cobbles to determine if this material represented Spanish architecture.

Confirmation of the ruins of Fort Guijarros caused a change in field methodology.

The crew devised a rectangular block grid with the west end directly over

the wet tiles and cobbles and the east end 19.69 feet away

(Figure 8.19). Screening of samples of the top 3.28 feet of yellow-tan

earth fill recovered low quantities of artifacts. The few artifacts recovered

included scuffed bottle glass, rusted sheet metal, and automobile parts.

Based on the very low potential for significant artifact features in this

fill deposit, the field director instructed the U.S. Navy backhoe operator

to remove the top 3.28 feet.

Figure 8.19 This exposure of the architectural ruin

shows the fort wall tiles collapsed down the cobblestone ramp that buttressed

the outside wall of the fort. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection,

P:81-332.

Field I measured 29.53 feet by 19.69 feet, and was gridded for six test

units 6.56 feet square, divided by 3.28-foot-wide balks. The balks provided

side wall profiles for each of the six units. The field strategy employed

one dig team with two people for each grid unit. A battery of ten screens

was arranged along the backhoe trench to screen the soil. Over 300 people

made up the crew that year. All man-made items recovered in the screens

were placed in bags marked by Field I, trench/gird unit, and level. These

field bags were then transported to the field lab for cleaning, sorting,

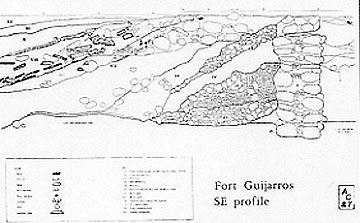

and cataloguing. Figure 8.20 Cross-section of the southeast wall of Fort Guijarros showing

the strata of the wall. Drawing courtesy of Stanley and Judy Berryman.

The strata started high at the west end of Field I and sloped down to

the east.

The elevation of the same strata at the west would, therefore, be substantially

lower on the east. To avoid potential errors in linking strata from unit

to unit, arbitrary locus numbers were assigned to natural layers as they

were encountered. For example, Unit 2, Locus 2 (broken fired tiles) at

an elevation of 8.04 feet at the top of the Spanish wall rubble at the

west end of Field I correlates directly to Unit 5, locus 8 (broken tiles)

at 4.92 feet at the east end (Figure 8.20).

Correlations of these loci to strata were made at the end of the field season in the Winter of 1981. For example, in this system, Unit 1, Locus 2 became Strata 8, as did Unit 5. The stratigraphic sequence followed the stages that architectural elements were installed on the beach at Ballast Point in 1795-1796. Under the supervision of Engineer Alberto de Cordobá, the laborers installed each element in layers of cobble, sand, tile, mortar, and whitewash to achieve the finished product. The stratigraphic sequence is essential to understand the physical appearance and structural integrity of Fort Guijarros. Figure 8.20 illustrates the sidewall cross-section of Field I, southeast wall. This report will only address the architectural sequences related to Fort Guijarros. Description of earth fill strata laid down by U.S. civilian whaling companies and U.S. Army can be found in other reports (May 1985a, 1985b, 1996; Donaldson and May 1996:60-70).

Contrafuera or Revestimento

Strata I through VI, designed by Engineer Alberto de Cordobá to

buttress the massive heavy masonry superstructure and cannon decks, are

important to the archaeological sequence. This architecture comprised

the following six elements:

1. Strata I. The first step in erecting Fort Guijarros involved marking

the outline in the beach sand and excavating a keyway trench for the foundations.

The Spanish work crew dug the keyways into the beach sand of Ballast Point.

No artifacts were present in the beach sand under Fort Guijarros to indicate

prior occupation by Spanish or Native American people prior to 1796. The

functional purpose of Strata I is found in de Lucuze’s 1772 treatise

on fortification (Quillin and Quillin 1988:3-7). The core wall stabilized

the massive interior earth/rock fill that supported the cannon deck and

merlón. A sloped battery face buttressed the core wall. This entire

association of the interior fill, core wall, and battery face is the contrafuera.

The term literally means against-away or against the outside. The angle

of the vertical length of Strata I records the battery face.

2. Keyway Trench. The keyway trench excavated into the beach sand of Ballast

Point to a depth of 1.8 feet below the 1796 beach surface (See

figure 8.15, base of Strata I). The 1981 investigation recorded

the original beach elevation at 2.48 feet above mean sea level (AMSL).

Seawater pooled in test holes in the beach sand surface at an elevation

of 1.64 feet. Presumably, the entire wall of Fort Guijarros was initially

marked out by excavated keyway trenches.

3. Internal Cobble Reinforcement. The keyway trench had been filled with

randomly placed cobbles and formed the foundation for Strata I (See

figure 8.20). The cobbles ranged from 3.96 to 7.92 inches in

diameter. A 1.2 in layer of black shell midden mortar coated the top of

the cobbles to bond them in place. The second tier consisted of large

crudely shaped sandstone blocks measuring from 9.84 to 17.76 inches across.

The sandstone blocks were embedded in the black shell midden mortar. Spanish

work crews erected Strata I as a vertical wall from the beach upward (Figure

8.21). Twelve tiers of cobblestone were exposed in the 1981 investigation.

The uncovered tiers rose in elevation above the beach and keyway trench

at to an elevation of 9.7 feet. Typical of the tiers, Tier 4 involved

a double row of rounded cobbles chinked with 1.92-3.84-inch rounded pebbles.

Each tier had been mortared with black shell midden mortar.

|

Figure 8.21 The feature is one of twelve layers of cobbles that went into building Strata I, the core wall. It was built inside the fort wall itself and served to strengthen the front part of the merlon. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:81-7278. |

4. Internal Wall Foundation Mortar. The black shell midden mortar was characterized

by crushed Ostrea lurida fragments speckled throughout the deposit. Occasional

metavolcanic hard hammer percussion flakes were recovered in this mortar,

indicating the Spanish mined the shell midden from a prehistoric site somewhere

nearby. The mix of shell, flakes, and midden must have produced sufficient

bonding properties to be selected as a wall mortar.

5. Sealed Inside the Wall. The selection of soft and organically rich prehistoric

shell midden for mortar would have posed serious structural problems if

the mortar had been exposed to rain and ocean surf. Strata I was intended

to be encased within other architectural elements and sealed from moisture.

Buttressed on both sides and topped by whitewashed cement mortar, the shell

midden mortar remained intact until the 1981 archaeological investigation.

6. Ruined Fort Surface 1851-1896. The top of Strata I exposed in 1981 represented

the surviving stump of a more elevated architectural feature. Analysis of

elevations on the 1851 U.S. Coast Survey map, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

1867 (See

figure 8.1), and the 1896 maps demonstrates approximately 11

feet of architecture was removed between 1851 and 1896.

Lt. Weeden’s U.S. Army Corps of Engineers construction of Fort

San Diego is believed to be responsible for this removal. Elevations recorded

on the U.S. Army 1873 Field of Fire maps provide a clue as to why Lt.

Weeden would have directed demolition; Fort Guijarros would have impeded

a clear field of fire from the 1873 U.S. Army artillery batteries.

Strata I ran the length of the cannon battery wall. A similar architectural

element would have paralleled Strata I approximately 20 feet west to the

interior to support the massive earth and cobble fill of the cannon deck

and merlón (not yet tested). To prevent Strata I from bursting

outward and collapsing, Spanish work crews heaped a massive cobble buttress

against Strata I to form the battery face (Figures

8.22 and 8.23). Lacking quarry stone to erect a more vertical battery

face, the heaped cobbles tumbled out to form a 45 to 60 degree slope (glacis).

Figure 8.22 Artist’s conception by Joyce Reading

in 1981. Although new findings have revealed that the cobblestone core

is in a different location and the wall is much larger, the glacis or

buttress ramp outside is made clear by this sketch. San Diego Union, August

25, 1981.

Figure 8.23 View west of wall (Strata V). The first layer of revestimento (glacis) cobbles were removed from Strata III. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:81-7272.

Internal wall components: Strata II, III, IV, V

The 1981 archaeological investigation cut a cross-section through the

contrafuera (See

figure 8.20). Thousands of 3.96- to 15.84-inch rounded cobbles

were heaped against the first six tiers of Strata I. Two distinct layers

of these cobbles have been labeled Strata II and III. Above Strata III

cobbles was a layer of tan sand (Strata IV) and another mass of small

cobblestones (Strata V). The battery face of Fort Guijarros formed a glacis

of cobblestones from the top of Tier 12 of Strata I sloped down to the

beach, which Spanish engineers called the revestimiento.

As the Spanish construction crew elevated the tiers of Strata I, they

also filled the interior side with alternating levels of sand and large

cobbles. The first level is clear white beach sand, believed to have served

to level the surface above the beach at Tier 2. To the right of Strata

I in Figure

8.8, layers of large cobblestones are recorded at Tiers 2,

3, and 6, which were better understood during the Field VIII investigation

exposing the top layer a full 32.81 feet west of the foundation core.

Supported by contrafuera on each side of the core wall, beds of large

cobbles sandwiched sand levels to form a strong foundation for the cannon

decks and heavy masonry merlones.

The archaeological remains of the merlones exist as collapsed rubble on

top of the sloping glacis of the contrafuera. Depicted in

Figure 8.20 as Stratum VI, VII, and VIII,

the architectural rubble posed a puzzle for archaeological interpretation

that required treating each masonry fragment as a puzzle piece to be analyzed

for interpretive reconstruction (Buchanan 1996; See

figure 8.21) which depended on that analysis and correlation

to engineering directions posed by de Lucuze.

The current hypothesis proposes that scavengers removed critical cobbles

and tile. Once weakened, the yellow sand fill behind the merlón

would have poured down the cobblestone slope covering the beach below.

The tile masonry would have collapsed inward, or floated over the sand.

Scavengers would have further broken the tile mass, but the sudden deposition

of the merlón masonry protected more intact architecture (May 1996:13).

Strata VI

Strata VI was a yellow-tan sand identical to the yellow-tan fill sand

on the interior side of Strata I. This fill appears to have leaked through

or across Strata I and poured down to cover Strata V cobbles. No artifacts

were recovered in Strata VI, indicating the sand was deposited on Strata

V during an episode when no one occupied the area. This deposition may

have occurred after Mexican demilitarization in 1835, when the authorities

no longer maintained the battery.

A mass of cobbles half way down the slope of Strata VI may have been dislodged

from Strata I or pushed from higher elevation of Strata V. These cobbles

in Strata VI appear larger than those observed in Strata V. These cobbles

may reflect decomposition of the battery face, as well as interior fill

sand leakage.

Strata VII

A massive deposit of slightly yellowed sand completely covered Strata

VI and spread east beyond the Field I excavation. A single white plate

sherd with a Pearl Ware glaze recovered from screening Strata VII provided

the only evidence to date deposition. The general lack of artifacts in

Strata VII indicates the deposition did not coincide with occupation of

the site, but occurred after the 1840s. The length of Strata VII, a full

19.69 feet east of Strata I, indicates a powerful single episode of dry

transport of material. This depositional process would be similar to a

landslide.

Comparison of Strata VI and VII soils suggest two distinct episodes of

architectural collapse. Strata VI dimensions indicate slow leakage, while

Strata VII dimensions indicate a sudden and powerful collapse of a massive

structure filled with loose sand (Figure 8.24).

|

Figure 8.24 This photograph shows a collapse episode of Strata VII and VIII rubble, as well as broken tiles with plaster. They tumbled in at different angles on top of yellow sand (Strata VI) and Strata V cobblestone glacis. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:81-7257. |

Strata VIII

A random mound of large cobbles mixed with dissolved and re-compacted reddish-tan

adobe block, shattered fragments of whitewashed cement mortar, and fragments

of fired adobe tile formed the upper portion of Strata VIII as it lay directly

on top of Stratum V, VI, and VII (See

figure 8.20). The cobbles correlate directly with cobbles in

Strata I, but no black shell midden mortar was recovered in Strata VIII.

Directly on top of the mound of cobbles lay a partially dissolved stack

of unfired adobe blocks, yellow-tan sand mixed with high quantities of fired

tile chips and whitewashed cement mortar fragments, and smaller cobbles.

Patches of sea grass, also known as eel grass, and beach sand were interspersed

among the cobbles. See grass lives in brackish water estuaries, such as

would have been found 1 to 2 miles north at the confluence of the San Diego

River and San Diego Bay. The species does not exist near the more saline

mouth of the harbor near Ballast Point. Heavy discharge of the San Diego

River dislodges eelgrass flotsam and transports the grass along with driftwood

toward the mouth of the bay. The eelgrass in Strata VIII represents an episode

of heavy San Diego River discharge.

Loose clean beach sand is not indicative of estuary environments. The San

Diego River and Sweetwater River six miles to the east transport organic

sediments that decompose in estuarine eel grass and rocky settings. The

result is a more loamy sand than found closer to littoral beaches. Heavy

wave action and surf scouring cleans littoral sand of loamy sediments, leaving

white beach sand.

Removal of the unfired adobe and fill sand in Strata VIII revealed a tumbled

scree of dozens of fired adobe tiles, large sections of whitewashed mortar,

and reconstituted unfired adobe. A few large cobbles were mixed among the

fired tile mass. The volume of fired tiles increased on the western half

of Field I. Large quantities of sea grass matting and loose beach sand were

mixed among the fired adobe tiles in Strata VIII.

To obtain a sample of fired adobe tiles and whitewashed cement mortar for

architectural interpretation, all architectural remains in Units 1, 2, 3,

and Balk Units 1W, 2W, 3W were recovered. The analysis of these tiles is

reported elsewhere (Buchanan 1996).

All architectural remains exposed in Units 4, 5, 6 and Balk Units 1S, 2S,

3S, 4W, 5W, 6W, 1SW, 2SW, 3SW were left in situ for future scientific inquiry.

These were mapped, photographed, and designated elevations. A re-examination

of Field I in 1987 re-mapped these tiles (Buchanan 2005).

Strata VIII represents the final collapse episode for the merlones. The

presence of sea grass and patches of loose beach sand provide clues to the

process of collapse. Weakened by Strata VI leakage and massive Strata VII

landslide, high ocean surf coincident with heavy San Diego River discharge

would account for the sea grass and beach sand. A wet winter storm probably

caused the final collapse of the merlones at Fort Guijarros. The association

of a Pearl Ware sherd suggests this occurred mid-19th century.

As a footnote to the archaeology at Field I, the bulk of the architectural

samples recovered in 1981 and 1982 at Fields I and III were returned to

Field I in 1987. These were placed in the northeast corner in line with

the former backhoe trench. The returned specimens included hundreds of small

fired tile chips and fragments, paper sacks of whitewashed mortar, and a

dozen or so complete tiles. The area was marked with 1987 copper U.S. coins

and two modern machine-made bottles. These specimens were determined not

necessary for long-term scientific research.

Field II: Second set of architectural data

The 1982 field season designed an excavation strategy to obtain improved

Fort Guijarros architectural information. Tangent to the West End of Field

I, Field II measured 9.84 feet by 9.84 feet. An asphalt road installed by

the U.S. Navy in December 1981 had restricted the north boundary of the

sample area. A concrete deposit installed as a base for the 1975 boulder

rip-rap sea wall constricted investigation and limited archaeological access

to the south.

The east side of Field II was a southern extension of Strata I from Field

I. All of Strata I was left in place at Field II. At 0.1-0.3 inches, large

chunks of concrete rubble blocked deeper excavation. Soil in Field II coincided

with post 1924 U.S. Army deposition of the concrete rubble. Excavation of

Field II terminated at the rubble.

Field III: Test for activities outside the wall

Simultaneous with the Field II investigation, the 1982 field season designed an excavation strategy to search for Spanish architecture or occupation features on the beach east of the Fort Guijarros glacis (Figures 8.25 and 8.26). Anticipated activities would have been occupation and refuse deposits, metal and carpentry workshop activities, livestock agriculture, and boatyard activities associated with the Spanish flatboat that transported the fired tile, lumber, and cement from the Presidio.

Figure 8.25 A Birdseye View of Fort Guijarros. Jay Wegter. 1990. This hypothetical view of Fort Guijarros shows the target area of Field III. The goal was to test for behavioral activities on or around the glacis and beach beyond the Fort. Instead, an American whaling camp from a much later time period was encountered.

Figure 8.26 Soldiers at Fort Guijarros by Jay Wegter. 1990. This hypothetical interpretation shows how the outside of the Fort may have appeared. Note the sloping walls of the exterior of the Fort.

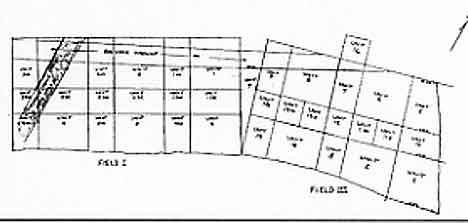

Field III measured 16.4 feet (north-south) by 29.53 feet (west-east) (Figure 8.27). The vast majority of Field III consisted of extensions of Stratum X (civilian shore whaling) and Strata XI and XII (U.S. Army) earth fill (May 1985:1-24; 1986:73-90; 1996:41-58). At the bottom, Stratum VIII rubble from Fort Guijarros scattered widely over sterile beach sand. Sample test pits in the beach sand encountered seawater but no artifacts.

Figure 8.27 General unit configuration for Field I and Field III, excerpted from C. Fred Buchanan’s Key Map–Field I & III. The reason the two grids are not in alignment is that nearby Navy equipment interfered with magnetic readings during the first ten years of the investigations.

Field III exhibited intensive wave scouring at Stratum VIII. As much as

2.62 feet of sterile beach sand separated individual tiles. All the tiles

were eroded by wave action, but fragments of whitewashed cement mortar

were also present in the sand. All the fired adobe tiles were recovered

for analysis, but most were returned to Field I in 1987 following analysis.

Field III demonstrated no Spanish architecture or other activities east

of the contrafuera (revestimento) and glacis on Ballast Point. Evidence

of activities that had occurred there have been scoured away by ocean

surf and heavy discharge of the San Diego River.

Field IV

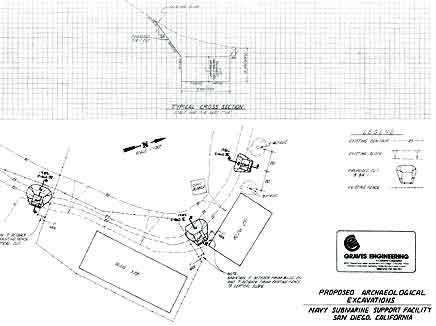

The 1983 field season tested hypotheses regarding the boundaries of archaeological deposits associated with Spanish and Mexican soldier occupation inside the wall of Fort Guijarros. Analysis of elevation contour lines on the 1867 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map of Ballast Point (See figure 8.1) revealed a man-made graded cut in the Point Loma hillside, a large level pad behind the portion of Fort Guijarros exposed in 1981, and a south berm along Ballast Point that linked with the fort. The Field IV test was placed north of the 1981 asphalt road and on the south face of the 1873 Fort San Diego and 1898 U.S. Army Battery Wilkeson (Figure 8.28). The purpose was to learn how the Spanish used the area behind the wall.

Figure 8.28 Civil Engineer Marty Byrne prepared this

design for deep test pits at the request of the Navy Civil Engineer. Once

approved, the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation had to design sufficient

shoring to meet the requirements of the Navy Safety Officer. The actual

location of Field VI was approximately fifty feet north of Byrne’s

proposal in order to avoid interfering with Navy operations. The Field

V pit was more to the left once the Navy demolished Building 251 (“The

Dolphin Club”).

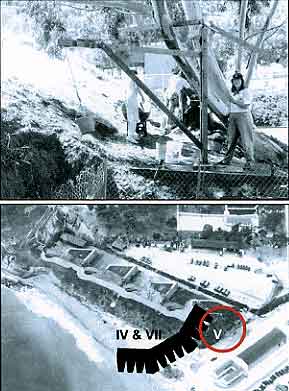

The Base Civil Engineer required an engineering drawing prepared to design safe excavation into the earth fill of Battery Wilkeson (Figure 8.28). Civil Engineer Marty Byrne of Graves Engineering prepared the drawing. A mechanical bobcat skip loader cut and shaped the excavation site. Heavy timber shoring locked the 20-foot-high cut in place and shored the excavation below 4 feet, in accordance with safety laws (Figure 8.29).

Figure 8.29 This view shows the heavy shoring necessary

to create a safe working environment deep below the 20th-century fill

that covers the mid-19th-century to late 18th-century trash deposits behind

the walls of Fort Guijarros in Field IV. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation

Photo Collection, P:84-636

A hand-crane erected on the wood shoring hauled metal

buckets of soil from the excavation (Figure 8.30).

All soil was screened through 1/4-inch mesh, but very few artifacts were

recovered in the first 6.56 feet. A single amber glass medicine bottle

dated the first 4.92 feet to after 1898.

Figure

8.30 Top: View of Andrea McKee at the wooden crane used to lower and raise

buckets in Fields IV, V, VI, and VII. Bottom: Composite using 1943 aerial

photograph of United States Army Fort Rosecrans Coast Artillery Battery

Wilkeson with Donaldson’s Fort Guijarros postulated location as

an overlay to show location of Field IV, V, and VII excavation areas indicated

by red circle. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:86-7181

and P:86-1033-16.

A large cast concrete drain from Lt. Weeden’s 1873-1874 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers construction of Fort San Diego appeared at 6.56 feet below the existing parking surface. The drain feature was left in situ for future scientific investigation. The base of the drain dated the surface of the ground to 1874. Directly below the base of the 1873-1874 drain, a bed of alluvial gravel covered the entire surface. This 7.92-inch-thick deposit (Locus 7) is believed to have been installed by Lt. Weeden to form a base for the drain installation. A single glass wall sherd of a 1860s schnapps bottle supports this interpretation.

Buried anaerobic pond clay deposit with Spanish trash.

Under the Locus 7 gravel deposit, a thin layer of wet, fine, greasy micaceous gray clay with black patches of decomposed woody vegetation and dark seeds formed Locus 8. The clay is similar to estuarine marsh ponds. A few marine shells and one fragment of a water-worn Spanish roof tile were embedded in the clay (Figure 8.31). Directly under the clay deposit, a wet gray sand of medium to coarse grains mixed with marine shell, Spanish tile, mortar fragments, and rock fragments formed Locus 9. The sand in Locus 9 was coarser than the surrounding beach sand. Hydraulic sorting of the Locus 9 sand indicates San Diego River deposition.

Figure 8.31 Spanish roof tile fragment. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:84-636.

Fort Guijarros trash feature

At a depth of 9.84 feet, a pit excavated through Locus 9 filled with a

4-to-9.84-inch-thick micaceous gray greasy clay deposit formed Locus 10.

Excavation released hundreds of fine dark vegetal seeds as the water table

rushed into the excavation. Sump-pumping lowered the water table in a

sterile hole southwest of Locus 10.

Locus 10 comprised a trash feature associated with the occupation of Fort

Guijarros. Large chunks of the micaceous gray greasy clay were removed

in buckets to be water-screened through 1/16-inch window mesh and 1/64-inch

geology screens. A total of 52.97 cubic feet of clay and artifacts were

recovered and water-screened.

The screens yielded rusted iron lumps, Spanish tile, splintered food bone,

Tivela stultorum Pismo clam shells, three sherds of a Tizon Brown Ware

jar, Asian Export Porcelain cup and platter sherds from the late 18th

to early 19th centuries, eight sherds of Mexican Majolica, Galera Ware,

wood, leather, bone button blanks, fish bone, animal teeth, and marine

shell.

Twigs, scraps of cut leather, and plant remains were placed in distilled

water baths to leach out salts. Once free of salt, the vegetal fragments

were dried and packaged with other vegetal remains. The cut leather scraps

were treated with Carbowax for long-term preservation and are now in the

temperature- and humidity-controlled Ballast Point Repository.

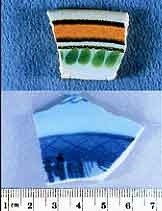

The Majolica included a sherd from a Monterey Polychrome soup plate, which

dates from 1800 to 1835 (Figure 8.32). Also

present were Puebla Blue-on-white and Aranama Tradition soup plates (1750-1835).

The Asian Export Porcelain included a large basal sherd of an Export Chinese

Canton Blue-on-white serving platter. The execution of the design and

detail work indicates early 19th-century manufacture. Other porcelain

included a hand-painted cup rim (Figure 8.32).

Upon removal of the last remains of Locus 10, test holes were excavated

through sterile beach sand to the water table. Metal probes as deep as

3.28 feet confirmed the determination of sterile sand below the trash

pit.

Figure 8.32 Top: This broken piece of an Aranama Polychrome

Tradition soup plate is classic early 19th-century Mexican Majolica. The

black accent surrounding the orange band and the green interior dots characterize

this type as dating from 1800-1835. Bottom: This Chinese Canton Trade

Ware serving platter fragment is a style that dates from a Manilla Galleon

supply ship in the late 18th century. Both sherds were recovered in an

anerobic pond clay deposit with other Spanish artifacts such as cut leather

strips, food bone, and Spanish tile. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation

Photo Collection, P:96-3581 and P:95-1770.

Following the discovery of a Spanish/Mexican trash feature behind the walls of Fort Guijarros, the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation and U.S. Navy collaborated in a long-term effort to define the extent of Spanish and Mexican behavioral activities surrounding the fort. The 1983 investigation of Field IV demonstrated the earth fill in front of 1898 U.S. Army Battery Wilkeson covered significant archaeological features associated with Fort Guijarros. The Monterey Polychrome and Canton Blue-on-white ceramic artifacts date the trash feature to the Fort Guijarros occupation between 1796 and 1835.

Field V: Test behind Building 539 Fire Station

A second investigation in 1983 tested an area 25 feet north of the northeast

corner of Building 539 in search of the northern extension of Fort Guijarros

architecture. This excavation was situated in direct line with the contrafuera

detected at Field I. Excavation at Field V provided no evidence the portion

of Fort Guijarros exposed in Field I is the north wing. At about 5.91

feet in depth, a dark brown to black soil with small rounded pebbles appeared.

Locus 2 contained Astrea undosa, Chione undatella, Haliotis ssp, Pteropurpura

ssp, and Tivela stultorum marine shell. Small fish bones, small Spanish

tile chips, and fragments of a Chinese brown-glazed vegetable jar dated

this deposit to the 1858-1886 whaling and Chinese occupation of the Fort

Guijarros site. Below Locus 2, wet beach sand with Astrea undosa and Ostrea

lurida marine shell and a few splintered cattle bones formed Locus 3.

Excavation to a depth of 6.56 feet at Field V failed to detect Spanish

architecture or trash features.

Field VI: Test north of Field V

The 1986 investigation of Field VI searched for Spanish or Mexican residential activity areas associated with Fort Guijarros along the bay shore. This 13.12-foot-square field block was located west of the asphalt parking lot, between two existing eucalyptus trees and on the east flank of the 1898 U.S. Army Battery Wilkeson (Figure 8.33). As in the design and execution of Field IV, heavy wood shoring protected the excavation crew from a cave-in. A wooden crane served to haul out buckets of earth.

Figure 8.33 Field VIII dig crew. Unidentified person

on the upper left; Jim Royle on the right. C. Fred Buchanan sits in the

foreground. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:93-1068.

From surface to 6.89 feet, Locus 1 proved to be medium to dark brown

loam mixed with automobile parts, U.S. Army glazed sewer tile, concrete,

rusted metal, machine-made bottle glass, a tree stump, and a white-painted

rock. The saw cut tree stump and rock were labeled Feature 1, and interpreted

as a Fort Rosecrans landscape feature. The artifacts date Locus 1 to post-1902

U.S. Army Fort Rosecrans occupation. Several hard hammer flakes, bones

and marine shell recovered in this deposit are secondary deposition and

not associated with the U.S. Army primary occupation.

At 6.89 feet to 8.2 feet below the parking lot, Feature 2 consisted of

a 0.84-to-3.96-inch-thick clay mixed with marine shell, splintered bone,

and 9 Spanish tiles. Faunal analyst Paula Reynolds identified the bone

as primarily donkey skull. Feature 2 may represent Spanish occupational

refuse, but the density of recoveries is not significant enough for scientific

study. Test holes in the sterile sand below yielded the water table at

8.86 feet deep.

Field VII

The 1983 field season placed a block of excavation units 11.48 feet (west-east)

by 6.56 feet (north-south) 6.56 feet west of Field IV to make a second

attempt at locating the Spanish barracks or kitchen behind Fort Guijarros.

A wooden hand crane was used to haul out soil.

From surface to 3.94, Locus 1 consisted of interbedded layers of yellow

and black soils mixed with occasional prehistoric fire-cracked rocks,

Spanish tile, marine shell, and a small caliber rim-fire bullet shell.

Locus 1 dates to the 1873-1874 construction of Fort San Diego. From 3.94

to 7.22 feet, Locus 2 consisted of a yellow-tan sand mixed with angular

rocks, sandy clay, and specks of red clay tile. Eighteen fire-broken rocks,

five hard hammer percussion flakes, one sherd of Tizon Brown Ware, and

two pieces of red clay were scattered widely about the deposit.

At 7.22 feet, a light brown sand interbedded with mottled yellow and brown

soil formed Locus 3. Mature Ostrea lurida and Astrea undosa marine shell,

Spanish roof tile, and traces of decomposed wood were spread within Locus

3. From 7.22 to 8.2 feet, Locus 4 consisted of white sand mixed with angular

and rounded rocks, rusted metal, Argopecten aequisulcatus, Ostrea lurida,

and Chione undatella marine shell, Spanish tile fragments, splintered

animal bone, and large cobbles. Locus 4 dipped in the northeast corner

to 7.55 feet. From 7.38 and 7.55 to 8.2 feet, a thin layer of dark gray

sand that blended to a mottled dark clay formed Locus 5. The clay and

earth layer contained pieces of charcoal, organic plant matting, Spanish

tile, splintered food bone, and marine shell. Locus 3 penetrated Locus

5 to 7.38 feet. At 8.3 feet, a thin light tan sand lens formed Locus 6.

Hints at metal artifacts appeared as iron rust stains.

From 8.2 to 7.38 feet in depth, a Spanish trash feature of gray greasy

clay, decomposed plant remains, rusted iron smears, gravel and charcoal,

Spanish tile, and splintered food bone characterized Locus 7. Removed

in large chunks for water-screening in 1/16-inch mesh, these organic-rich

materials yielded scraps of cut leather that were desalted and treated

with Carbowax. Seeds and plant remains were desalted and dried for later

analysis. The anaerobic wet clay environment preserved leather and wood.

Locus 7 also yielded Monterey Polychrome Majolica from the 1800 to 1835

time period, Mexican Galera Ware, and early 19th century Canton Blue-on-white

Asian Export Porcelain. Over 150 fragments of Spanish floor and roof tile

were recovered, most of which exhibited erosion from immersion in water.

The roof tiles provide tantalizing evidence for a Spanish building nearby.

The ceramic and food remains indicate the building to be the kitchen

.

Reynolds also analyzed the food bone from Locus 7. She quantified 717

pieces of bone weighing a total of 3,862.8 grams. In comparison, the Spanish

feature in Field IV yielded 1,759 bone pieces weighing 4,463.65 grams.

Given the similarities and proximity of these two features, the bone samples

were combined to yield 142 cattle (43%), 7 sheep (2%), 2 pig (-1%), and

1 horse (-1% ) specimens. A total of 129 or 85% were cut with cleaver

and 20 (13%) exhibited knife marks. This analysis also demonstrated that

133 or 67% of the cattle bones were plate or brisket cuts, 15 (7%) were

short loin (back), 12 (6%) were chuck (shoulder), and 9 (5%) were hindshank.

These data indicate a high incidence of slaughtering waste on site, rather

than transportation of cut meat from the Presidio five miles north.

The investigation at Field VII substantiated the presence of the Fort Guijarros military kitchen west of the artillery battery. Future investigation of larger portions of this area should reveal the barracks, kitchen, and perhaps the storehouses. The primary challenge to those investigations will be the U.S. Army fill at a depth of 8.2 to 9.84 feet which will need to be penetrated and shored prior to archaeology work.

Field VIII

The 1989 field season was designed to obtain a second sample of the contrafuera

of Fort Guijarros and to obtain measurements that would resolve architectural

questions regarding the composition of the merlones. This field block

measured 91.86 by 16.4 feet in size. The excavation was planned for several

years of work in order to maximize field measurement and provide ample

time to carefully excavate the U.S. Army and shore whaling company fill

layers that cover the Spanish ruins.

The excavation of Field VIII continued until October of 1995 (Figure

8.33). The field strategy for Field VIII did not involve a cross-section

through the wall. The Research Design oriented removal of fill layers

to expose Strata VIII, map and photograph the tiles (Figures

8.34 and 8.35). Only select specimens of architectural samples

not recovered at Field I or tile art specimens were to be recovered.

Exposure of the top of the foundation core in the contrafuera measured

10.8 feet above Mean Low Low Water. The toe of the cobblestone glacis

measured 26.25 to 32.81 feet away from the foundation core. The toe elevation

measured 6.68 feet above Mean Low Low Water at 26.25 feet and 6.42 feet

above Mean Low Low Water at 32.81 feet.

Figure 8.34 Top: Ron May stands, C. Fred Buchanan stretches

across the unit, Anne Peter sits at the upper right, and two unidentified

crew members worked to the left at Field I in 1987. Bottom: Typical tile

rubble at Field VIII. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection,

P:87-2632 and P:95-3163.

Figure 8.35 Jim Royle on the left shows Charlene Henning

where to draw one of the tiles that he had just measured in the grid beneath

him. They re-mapped Field I in 1987 so C. Fred Buchanan could apply his

architectural code for later analysis and interpretation. Fort Guijarros

Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:87-2540.

Once the tile rubble had been mapped, the pieces were lifted, carefully

examined, and stacked to one side (Figure 8.35).

The cleaned cobblestone glacis received a second set of measurements.

From the top of the contrafuera, a string had been pulled level at 10.8

feet above Mean Low Low Water. Plumb lines were then measured. At 5.41

feet along the line, the cobblestone glacis measured 10.24 feet above

Mean Low Low Water. At 10.17 feet along the line, the cobblestone glacis

measured 8.89 feet above Mean Low Low Water.

The above measurements and field observations provide a second set of

data to substantiate the contrafuera consisted of the foundation core

buttressed by a slope of cobblestones. The slope dropped 1.9 feet over

a distance of 10.17 feet.

The secondary objective of the Field VIII investigation was to seek artifactual

evidence in the merlones rubble to (a) determine the composition of the

merlones battery face and (b) seek ceramic artifacts to date the demolition

or collapse of the merlones. The 1981 and 1987 revisit to Field I recovered

only one English white ware ceramic sherd of vague 19th-century vintage.

The Strata VIII soil in Field VIII was identical to the soil exposed in

Field I. The following points are made from the Field VIII data:

1. Both contained melted and reconstituted unfired adobe block mixed with

beach sand and mats of sea grass.

2. Two good samples of mud-mortared adobe block joints were recovered

in 1995 to substantiate the role of adobe block in the construction of

the merlones.

3. The low volume of unfired adobe block in the Strata VIII matrix substantiates

the Field I observation that adobe framed but did not fill the merlones;

sand filled the interior.

4. The presence of yellow-tan sand in relative abundance below the Strata

VIII correlates to Stratum VI and VII in Field I, which could have filled

the merlones and flowed down the glacis below the tile rubble.

Strata VIII at Field VIII confirmed the observation of Strata VIII at

Field I that very few artifacts were deposited during the decomposition

process of the wall. Detailed observation in Field VIII redefined the

soil to be primarily water-melted adobe that flowed and settled among

tile and mortar rubble from the merlones. The presence of white beach

sand and sea grass are strong evidence that the merlones collapsed during

a heavy flow of the San Diego River, during a high tide, and coincident

with wave action that deposited both the sand and sea grass. The single

Puebla Blue-on-white Majolica soup bowl sherd probably washed down with

the collapsed merlón. The single English white ware bowl sherd,

square nails, spike, and saw-cut food bone were probably deposited by

civilian whalers long after Fort Guijarros collapsed.

One of the most dramatic discoveries at Field VIII was the layer or bed

of hundreds of boulder-sized cobbles that lay inside the contrafuera and

supported the cannon deck (Figure 8.36).

Held behind the buttressed wall front, this feature prevented sliding

on the layers of sand fill above and below. With help from the crew, C.

Fred Buchanan mapped all the exposed cobbles in 1995.

Figure 8.36 View from the roof of Building 539, Navy Fire Station, looking southwest across Field VIII towards the tip of Point Loma. The field of excavation reveals a massive cobble layer set down by Spanish builders to support the Fort Guijarros wall superstructure. The grid square in the photograph was used for mapping. Photo by Mike Nabholz. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Photo Collection, P:89-280.

Conclusion

The 1981 to 1995 investigations by the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation

uncovered new information regarding the surviving remains of the 18th-century

Spanish fort on Ballast Point. Although an enormous effort has gone into

digging, architectural analysis, and reporting, a great deal more can

be learned by further investigations.

The field blocks revealed the walls to be enormous in breadth and very

complicated in construction. The various layers of mortared internal foundation

walls were buttressed by layers of huge cobbles and clear beach sand that

were held together by the plastered, fired clay tile façade, applied

to an un-fired adobe shell to form the wall merlón.

The interior was filled with beach sand and the entire structure remained

solid as long as no water penetrated the soft interior adobe. At some

time in the mid-19th century, water did pierce the walls and several massive

architectural landslides collapsed the merlones over the exterior sloping

buttress (contrafuera or revestimento).

Behind the gun deck, the actual structure buttressing the massive walls

remains unknown. Fields IV and VII yielded evidence of the kitchen, but

more work is needed to define the range of daily activities at the fort.

Later whaling companies operated atop the ruined mound and the United

States Army built an artillery battery in 1873 and filled in the beach

with debris and sand. The site slipped into obscurity until the Navy and

Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation joined forces in 1981 to investigate

the surviving elements of the fort.

References Cited

Bancroft, Hubert Howe

1886 History of California. A.L. Bancroft & Company, San Francisco.

Buchanan, C. Frederick

1996 Fort Guijarros Structural Analysis Preliminary Report; Facts and

Deductions. Fort Guijarros Journal (2). Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation,

San Diego.

Chapman, Charles E.

1921 The History of California: The Spanish Period. The Macmillan Company,

New York.

Colston, Stephen A.

1982 San Joaquin: A Preliminary Historical Study of the Fortification

at San Diego’s Punta de Guijarros. Fort Guijarros. Tenth Annual

Cabrillo Historic Seminar, 61-83. Cabrillo Historic Association, San Diego.

Cook, Warren L.

1973 Flood Tide of Empire: Spain in the Pacific Northwest, 1593-1819.

Yale University Press, New Haven.

Corps of Engineers Map of the Site of Proposed Battery, Ballast Point,

Surveyed under the direction of Major Charles E. L. B. Davis, Corps of

Engineers

Sept.-Oct. 1896 Fort Guijarros Map Collection, M:WILK-74 (1 of 3).

Cutter, Donald C.

1989 Search for Fort Guijarros: A Personal Research Effort Sponsored by

the Casa de España en San Diego, the Spanish Consulate in Los Angeles,

and Iberia Airlines. Fort Guijarros Quarterly (3)4:6 Fort Guijarros Museum

Foundation, San Diego.

Donaldson, Milford Wayne and Ronald V. May

1996 Nomination of Fort Guijarros, CASDI-12000 to The National Register

of Historic Places and Preliminary Determination of the Site Boundaries.

Manuscript on file, U.S. Department of the Navy, San Diego.

Floyd, Susan

1995 The Case of the Silver Spoons, or the White Elephant of Nootka. Fort

Guijarros Journal. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation, San Diego.

May, Ronald V.

1982 The Search for Fort Guijarros: An Archaeological Test of a Legendary

18th Century Spanish Fort in San Diego. Fort Guijarros 1(10):1-22. Tenth

Annual Cabrillo Historic Seminar.

1985a Schooners, Sloops and Ancient Mariners: Research Implications of

Shore Whaling in San Diego. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly

21(4):1-24. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly, Costa Mesa.

1985b The Fort That Never Was on

Ballast Point. Journal of San Diego History 36(2):121-136. San Diego Historical

Society, San Diego.

1985c The Guns of Point Loma: America’s First Sea Coast Artillery

Defense in San Diego. The Military on Point Loma. Cabrillo Historical

Association, San Diego.

1986 Dog Holes, Bomb-lances and Devil-fish: Boom Times for the San Diego

Whaling Industry. Journal of San Diego History (36)2:73-90. San Diego

Historical Society, San Diego.

1988 A Preliminary Report on the Summer-Fall 1988 Archaeological Field

Season at Ballast Point, San Diego, California. Fort Guijarros Quarterly

2(3):4-25. Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation, San Diego.

1994 Field VIII Archaeology Report for The 1989-1993 Seasons. Manuscript

on file, U.S. Department of the Navy, San Diego.

1995 Evidence for The Physical Appearance of 18th Century Spanish Cannon

Batteries in California. Fort Guijarros Journal 1:4-15. Fort Guijarros

Museum Foundation, San Diego.

1996 Research Design for the 1996 Investigation of the Interior Wall of

a1796 Spanish Cannon Battery, American Army Artifacts, and the Ballast

Point Whaling Station Located on the United States Naval Submarine Base,

San Diego. Manuscript on file, U.S. Department of the Navy, San Diego.

Quillin, Col. Frank (ret.) and Margaret Quillin

1988 A Translation of Chapter VI of Don Pedro de Lucuze’s 1772 Principios

de Fortificación as it Relates to the Design of the Fort at Punta

de Guijarros, San Diego, California. Fort Guijarros Quarterly (2)1:3-7).

Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation, San Diego.

Sandels, G.M. Waseurtz af

1945 A Sojourn in California by the King’s Orphan: The Travels and

Sketches of G.M. Waseurtz af Sandels, A Swedish Gentleman Who Visited

California in 1842-1843. Grabhorn Press, San Francisco.