Home

Mission Statement

Editorial Policy

Submission Information

Volume One

Casual Papers

Fort Guijarros

Volume Two

Postulation of the Positioning of the Fort Guijarros Defense Walls

Milford Wayne Donaldson

While preparing the Fort Guijarros National Register nomination application,

it became apparent that a tremendous amount of archaeological work has

been done concerning the Fort’s architecture. However, there had

not been a serious discussion on the actual position and orientation of

the Fort’s walls. The importance of this positioning in National

Register nomination is to prevent the unwarranted destruction of possible

valuable archaeological remains associated with Fort Guijarros either

on the land or underwater. Prior to the preparation of the nomination,

it was believed that the planform of the Fort’s walls existed only

on land and did not project into the current coast line. However, the

past archaeological investigation by Ron May detailed the position of

one wall and its heading very accurately. This one section of the wall,

along with the consideration of Spain’s standard defense strategies

and the battle of San Diego Bay, provided the following postulation of

the positioning of Fort Guarjarros’ defense walls.

Construction of the fort was evidently slow, for in December of 1796,

nearly two years after the site had been selected, the Spanish Extraordinary

Engineer, Alberto de Córdoba, inspected the incomplete defenses

at San Diego and was not impressed. However, as he arrived amidst discussions

concerning the disposition of the Fort, it seems that construction had

only just begun. In 1797, Córdoba recommended to Governor Borica

that the fort should not be circular. It was also believed that Córdoba

ordered two wings be added to the fort so that the battery could support

a total of ten 6-inch cannons instead of eight. The design and construction

of Fort Guijarros are not known with any certainty, except for the fact

that that it did exist at the base of Ballast Point. The placement was

strategically located to align the cannons at broadsides with the narrow

passage off the eastern tip of the point. The Fort was placed low so that

cannon balls could be “skipped” across the water to strike

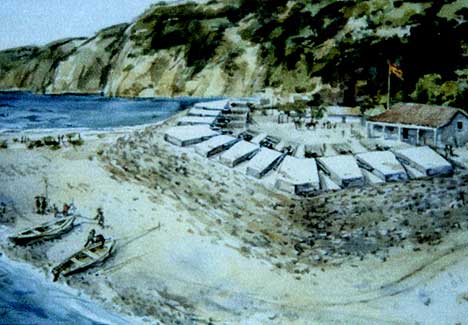

a ship at the water line (Figures 7.1 and 7.2).

Figure 7.1 Fort Guijarros. 1990. Watercolor by Jay

Wegter. Hypothetical depiction of what the fort may have looked like based

upon archaeological and historical interpretation.

Figure 7.2 La Esplanada. 1990. Watercolor by Jay Wegter.

Hypothetical depiction of the soldiers at Fort Guijarros looking out at

the entrance to San Diego Bay.

The environmental setting has changed substantially since completion of

Fort Guijarros in 1796. Though the appearance and exact disposition of

the original Fort are unclear, archaeological investigation has revealed

important information about the nature of the Fort’s construction

(May 1982: 15-17). The foundation core rose approximately 6.5 feet above

the original beach level, and there was a cobble-covered fill slope which

the Spanish called a rampa along the outside of the wall. On the inside

was an earth and cobble-filled platform called the esplanade del cañones.

This was the area where the cannons rolled as they fired through the crenellations

in the wall. The upper walls, or superstructure, were made of cobble and

adobe and were about three feet above the esplanade del cañones.

Over 9,000 pesos were allocated in 1797 to complete the battery, magazine,

and barracks and to construct a flatboat to ward off imminent English

invasions. In 1801, a road was also constructed to connect the Fort with

the Presidio. Despite these efforts, Spanish authorities acknowledged

that San Diego’s fortifications were less than formidable. In the

event of an invasion, orders were for the guns to be spiked, the powder

and provisions burned, and the soldiers to flee. Though no invasion ensued,

the English threat helped rally efforts to complete the Fort. When Spain

announced its peace with England and Russia in 1802, fear of military

action subsided.

Ironically, it was not a British war ship but an American merchant brig

which brought about the now famous Battle of San Diego Bay in 1803. The

Lelia Byrd sailed in from Hamburg, loaded with European merchandise which

it intended to trade for otter pelts, despite Spanish trade prohibitions

in the Californias. The otter pelts had a great allure for merchants.

One pelt could sell for as much as 40 American dollars in China. Though

sale of these pelts was prohibited to foreigners by Spanish law, some

Spanish military authorities were known to participate in the lucrative

trade regardless. When William Shaler, Lelia Byrd’s master, and

Richard J. Clevland, the brig’s co-owner, heard that some 491 pelts

had been confiscated for illegal trade and were being held in a warehouse

at the Presidio de San Diego, they set sail for the port in an attempt

to obtain them. The Lelia Byrd sailed past Point Guijarros without challenge

and anchored about one mile inside the entrance and three miles from the

town and Presidio, within hailing distance of the beach.

Apparently, some of the authorities in San Diego were more scrupulous

than those in other California ports; three of Cleveland's men were detained

for trying to bribe a Spanish officer. Cleveland and a few other men managed

to rescue the three would-be smugglers at gun point. The captured Spanish

guards were placed on their ship as hostages. Shaler was promptly underway,

but made little headway due to the light morning wind. Approximately half

a mile north of the point, Shaler ordered six three-pound swivel guns

on the starboard side to be armed. The Lelia Byrd was under fire fully

three-quarters of an hour before arriving near enough to reach the Fort

with their small guns.

Swivel-guns were not used for long distance cannoneering; the ship held

its fire until within musket-range of the fort (approximately 100 yards,

or about where the Submarine Base swimming pool is now located); a large

target at that range. As they tried to make an escape past Fort Guijarros,

cannon fire was exchanged on both sides. The Fort sustained no real damage,

but the Lelia Byrd reportedly took two balls in the hull at water-level

and suffered damage to her rigging.

The brig did manage to make it out of the harbor, however, releasing its

hostages just out of range of the fort and sailing south to San Quintín

Bay for repairs. Despite the damages to the vessel, Cleveland, the co-owner

of the Lelia Byrd, described the Fort which had fired upon him as "a

sorry battery of eight-pounders… at present it does not merit the

least consideration as a fortification, but with a little expense might

be made capable of defending this fine harbor" (Bancroft 1886:103).

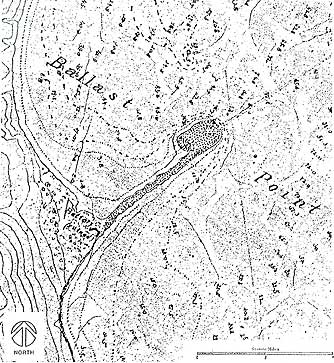

The importance of the battle, along with the 1851 map of Ballast Point

as prepared by the U.S. Coast Survey, offers insight as to the probable

geometry of the fort and the direction of cannon fire. Certain orientation

has been concluded given the firing headings and position of the excavated

contrafuera. In 1851, A.M. Harrison prepared The Tracing of the Plane

Table Sheet of San Diego, and the final map and survey were completed

by R.D. Cutts and George Davidson in 1853 (Figure 7.3). Harrison's tracing

shows a Battery Ruin in a curious expanded U-shaped form. This detail

was altered in Cutts and Davidson's map.

Figure 7.3 San Diego Bay, California. “Battery

(ruined)”; Enlarged detail of the tracing on the plan table sheet

of the San Diego Bay, California. Survey by A.M. Harrison. Source: U.S.

Coast Survey, 1851.

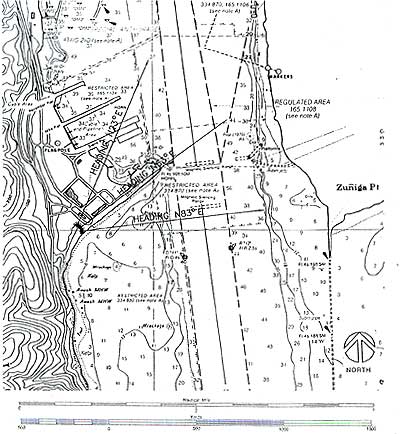

Indications of the Fort’s ruins are not found on the 1857 U.S. Coast

Survey. Based upon the events of the Battle of San Diego Bay and the apparent

geometry of the Fort, a probable plan was developed showing the cannon

firing headings (Figure 7.4). These headings protected three main critical

areas: (1) the entrance to the bay, (2) Ballast Point (in case of a possible

landing) and (3) the area around the point where the ships had to sail

due to the sounding depths as recorded on the 1783 La Pérouse Survey

Map No. 35.

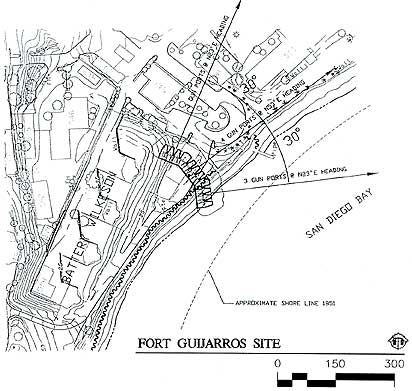

Figure 7.4 Fort Guijarros Probable Plan. Fort Guijarros Probable Plan shows cannon firing headings placed on NOAA San Diego Bay map with sounding depths. Source: NOAA and Architect Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, Inc., dated 1996.

Anchorages are indicated around the point and closer to the mainland.

Due to the sandbars, it was not considered safe to sail up the center

of bay at this time. In her escape, the Lelia Byrd had to go down the

east coast of Point Loma and around Ballast Point before heading out to

open sea. The position of the Fort's guns, regardless of the skill of

the cannoneers, offered an excellent chance to do damage to any ship confined

within these narrow passages.

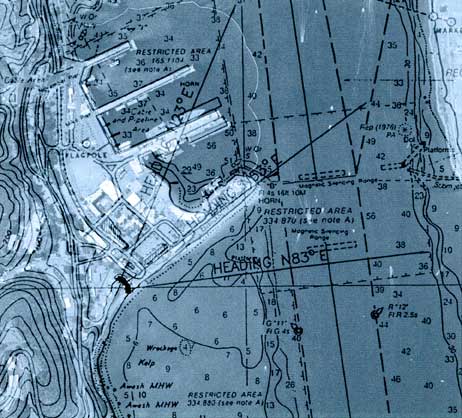

The positions of the gunports also appear to agree with this postulation.

The center four main guns point directly up Ballast Point to protect against

foreign hostile landings (Figures 7.5 and 7.6).

Figure 7.5 Fort Guijarros Site Plan with Cannon Firing Headings Composite Overlay. Site plan showing the fort with cannon firing headings superimposed over the present day topography. Source: Architect Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, Inc., dated 1996 and Google Earth 2005 satellite imagery.

Figure 7.6 Fort Guijarros Site Plan. Site plan showing the fort with cannon firing headings. Source: Architect Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, Inc., dated 1996.

The shoreline in the 1850s was considerably further out into the bay. A 1900s photograph of Battery Wilkeson looking towards Ballast Point confirms that even at this late date the shoreline was farther out in the bay (Figure 7.7).

Figure 7.7 Battery Wilkeson. This view depicts Battery

Wilkeson and Fetterman overlooking the 1890 lighthouse and whaler’s

warehouses at the eastern tip of Ballast Point. The ruins of Fort Guijarros

would be to the right of the largest gun battery, Battery Wilkeson. Source:

Architect Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, Inc.

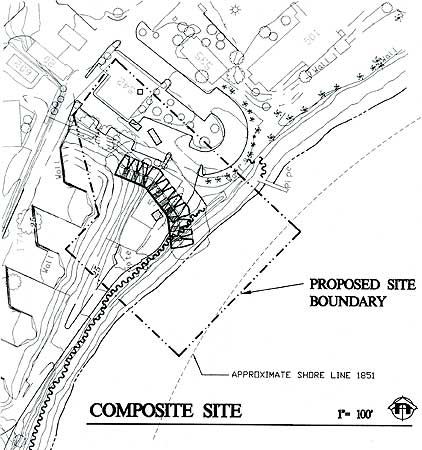

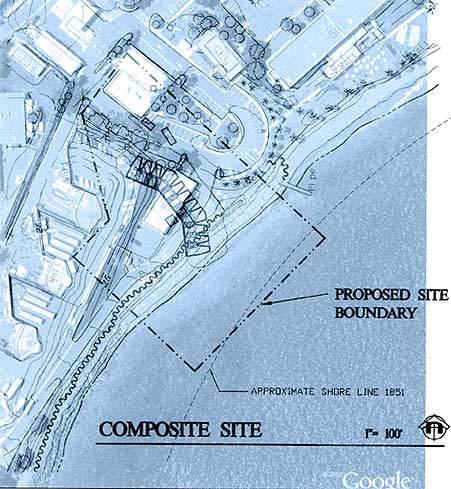

Should this nomination be recorded as a National Register of Historic Places site, it would require that further detailed underwater archaeology be performed in the event of off-shore construction work in order to satisfy the Section 106 process. In the meantime, it would be exciting to perform additional archaeology under Building 539 (the Fire Station) to confirm the limits of the western wing of Fort Guijarros (Figures 7.8 and 7.9).

Figure 7.8 Fort Guijarros Composite Site. The composite site shows Fort Guijarros, Ballast Point Whaling Station, and the proposed site boundary. Source: Architect Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, Inc., dated 1996.

Figure 7.9 Fort Guijarros Composite Site Overlay. The

composite site overlay shows the proposed site boundary of Fort Guijarros

superimposed over the present-day topography. Source: Architect Milford

Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, Inc., dated 1996 and Google Earth 2005 satellite

imagery.

References Cited

Bancroft, Hubert Howe

1886 History of California. A.L. Bancroft & Company, San Francisco.

Corps of Engineers Map of the Site of Proposed Battery, Ballast Point,

Surveyed under the direction of Major Charles E. L. B. Davis, Corps of

Engineers,

Sept.-Oct. 1896. Fort Guijarros Map Collection, M:WILK-74 (1 of 3).

May, Ronald V.

1982 The Search for Fort Guijarros: An Archaeological Test of a Legendary

18th Century Spanish Fort in San Diego. Fort Guijarros 1(10):1-22. Tenth

Annual Cabrillo Historic Seminar.