Home

Mission Statement

Editorial Policy

Submission Information

Volume One

Casual Papers

Fort Guijarros

Volume Two

The Regional Consequences of Lake Cahuilla

Don Laylander

Many uncertainties surround the prehistoric chronology of Lake Cahuilla and the lifeways of the people who lived along its shores. Even more difficult questions concern the region-wide effects that may have resulted from the dramatic environmental transformations associated with the lake's rise and fall. Possible repercussions include the spread of technology, new distributions of languages and dialects, changes in subsistence strategies, population growth, increases in intra- and interregional trade, anomalies in settlement organization, and elevated levels of intercommunity violence. Although these repercussions are still primarily hypotheses to be tested, some of the regional patterns appear to be plausibly linked to the late prehistoric cycles of the lake.

The Characteristics of Lake Cahuilla as a Potential Causative Agent

Several features of the Lake Cahuilla phenomenon need to be considered in assessing its potential as a source for regional changes or cultural anomalies. These include the repetitive nature of the lake's changing levels, the time scales in which the changes occurred, the lake's geographical scale, and its effects on resources available for human use.

Cyclical Character

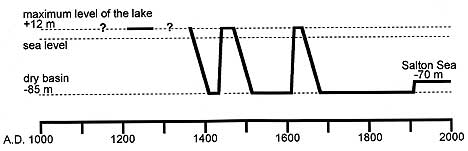

Until recently, it was commonly thought that the late prehistoric presence of Lake Cahuilla had been a single episode spanning at least five centuries, between about AD 1000 and 1500 (Rogers 1945). Subsequent evidence from radiocarbon dating and stratigraphic observations established that the lake's rise and fall were repeated events (Waters 1983; Wilke 1978). A minimum of three fillings and recessions occurred between about AD 1200 and 1700 (Figure 6.1; Laylander 1997a:64-68). This suggests a frequency of roughly one lacustrine cycle every 200 years, but that frequency may merely reflect the level of resolution that is presently obtainable from the radiocarbon dates. The possibility that additional cycles occurred during this period cannot be ruled out. There may have been earlier lacustrine episodes prior to AD 1200, although the question of their number and timing remains obscure (Love and Dahdul 2002; Waters 1980).

Figure 6.1 A tentative chronology for Lake Cahuilla

during the late prehistoric period.

Early models assumed that the rise and fall of the lake were unique events

and interpreted the connections between those events and various regional

archaeological and ethnographic phenomena accordingly. However, current

knowledge concerning the repetition of these events requires that such

interpretations be reconsidered. If the lake's first rise–whenever

it may have occurred–is proposed as having served as a stimulus

for various regional developments, a similar stimulus was likely exerted

several times subsequently. The lake's final recession in the late seventeenth

century should not be thought of as a unique event, except in hindsight

as a perspective following three dry centuries. Native responses attributed

to any one recession may have been repeated during several other periods.

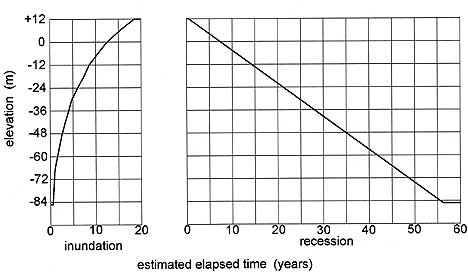

Time Scale

The duration of the processes of change associated with Lake Cahuilla is another significant dimension. The lake’s appearance and disappearance were not sudden or brief environmental events, like earthquakes, hurricanes, or floods. At a minimum, the filling of the lake would probably have taken about twenty years to complete, and its recession would have taken three times that span (Figure 6.2; Laylander 1997a:45-54; cf. Waters 1980, 1983; D. Weide 1976; Wilke 1978).

Figure 6.2 A scenario for the inundation and recession

of Lake Cahuilla, based on early twentieth century climate and hydrology

(Laylander 1997a:128).

These periods are too long in duration to have been bridged by the sorts

of emergency measures to manage subsistence that were a part of the normal

repertory for native cultures in western North America, such as using

stored foods or making temporary visits to relatives living outside the

affected region. On the other hand, the events were too abrupt and short-lived

to have been managed simply by the unconscious processes of gradual cultural

adaptation. In contrast to the situation with many important prehistoric

environmental shifts, such as rising sea levels or gradual climatic changes,

the people who lived through the various episodes of a rising or falling

lake were undoubtedly conscious of the changes that were happening around

them. It is also possible that oral traditions made them aware of the

pattern of previous lake cycles (see Laylander 2004a).

Within the main, decades-long episodes of inundation and recession, a

secondary sequence of changes occurred, so that the appearance and disappearance

of the lake did not represent simple events. Most of the lake’s

rise may have been too rapid for shoreline biological communities, in

particular marsh plants, to keep pace with its movements. The effects

of a rapidly rising lake on the populations of fish, shellfish, and water

birds remain uncertain. However, by the time the lake was nearly full,

its rate of rise must have slowed considerably, to 2 meters per year or

less compared to the rate of the lake's subsequent recession.

Once the lake was full, the shoreline may have stabilized for an indefinite

period. A degree of stability is suggested by the tufa deposits that formed

on rocks just below the lake's high water mark, by the well-developed

beach features in some areas, and by the numerous archaeological sites

that are associated with the maximum shoreline. How long the lake remained

at this level during each of its several fillings is unknown, although

a full lake was obviously present for much briefer periods than the 500-year

stand that was once suggested. Siltation of the lake’s relatively

low-gradient inlet channel that occurred once the lake had reached its

maximum level may have regularly diverted the Colorado River back to its

previous southward course fairly quickly. In any case, it seems likely

that the longer the stable maximum shoreline existed, the richer its associated

fauna and flora would have become.

The lake's recessions were slower than the rises, and they therefore had

a different character for the region’s prehistoric inhabitants.

Although complete desiccation could have been accomplished in about 60

years, archaeological evidence from fish remains attests that the receding

lake was refreshed by an inflow of water from the Colorado River on at

least one occasion (Schaefer 1986). The example of numerous small natural

floods of Colorado River water reaching the basin during the nineteenth

century suggests that such episodes might also have been common prehistorically

(Wilke 1978). Archaeological faunal remains of vegetation-adapted water

birds at recessional shoreline sites indicate that the floral community

was able to track the receding shoreline, which was therefore likely richer

in resources than the rising shoreline had been (Laylander 1997a:85-90).

On the negative side, recession was accompanied by gradually increasing

salinity levels, successively impoverishing and then eliminating the various

freshwater fauna and flora. However, there is evidence that fish and birds

continued to be exploitable at least as low as 55 meters below sea level,

or a minimum of about 40 years into the desiccation phase.

After the disappearance of the lake, climax biotic communities slowly

reestablished themselves on the dry lake bed. It has been suggested that

there was a separate stage in human adaptations to the basin after the

lake was gone but before mature mesquite groves established themselves

(Wilke 1978:13-14; cf. Schaefer et al. 1987:22). Contrary to this is the

fact that the exposure of the lake bed was a gradual process lasting decades,

and desert plant communities must have established themselves at successively

lower elevations above the retreating shoreline, even while the lake resources

were still available.

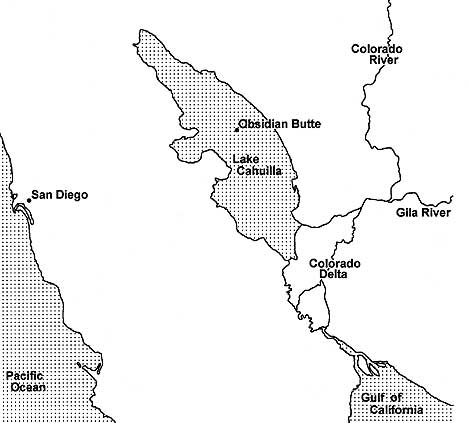

Geographical Scale

The size of Lake Cahuilla is also a significant dimension to be considered in assessing aboriginal responses to its cycles. About 180 km long and up to 50 km wide, the full lake had a surface area of about 5,500 km2 and a perimeter of more than 400 km of shoreline (Figure 6.3). The lower Colorado River delta included an additional 3,500 km2 of lands whose condition was directly linked with the fate of the lake.

Figure 6.3 Lake Cahuilla, the lower Colorado River,

the Colorado delta, and the surrounding region.

The lake's large size would have constrained the range of aboriginal options

for responding to its presence. If the lake and the delta had been substantially

smaller than they were, they might have been monopolized by a single community,

or at least by a single ethnolinguistic group. Under those circumstances,

the inhabitants of the lake basin and the delta might have minimized their

responses to the resource shifts that arose from the lake cycles. But

Lake Cahuilla’s great size almost inevitably made it an “international”

phenomenon. Different groups could have entered the basin independently

from several different directions. Diverse responses to the loss of the

lake's resources would likely have been produced by the diversity of the

hinterlands that lay in different directions outside the basin, as well

as by the competition among different groups.

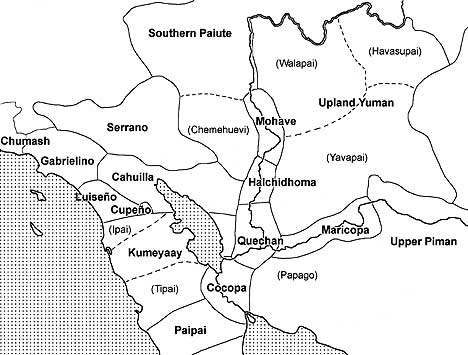

As documented ethnographically, the Lake Cahuilla basin and Colorado River

delta were split among at least three major ethnolinguistic groups: the

Cahuilla in the northern portion of the basin, the Kumeyaay in the southern

basin, and the Cocopa in the delta (Figure 6.4).

Ethnic distributions during earlier periods when the lake was present

are uncertain, but there are indications that at least three groups can

also be distinguished archaeologically within the basin. On the eastern

shoreline, eastern types of Lower Colorado Buffware ceramics suggest the

presence of River Yumans, similar to the ethnographically known Mohave,

Halchidhoma, and Quechan. On the northern and northwestern shoreline,

it is likely that Takic speakers, specifically the Cahuilla, were present,

as indicated by peculiarities in ceramics, arrow points, and shell beads.

On the southern and southwestern shoreline, Delta-California Yumans such

as the Kumeyaay and Cocopa were the most likely occupants. In sum, there

is no reason to posit the existence of a single Lake Cahuilla People or

expect that there would have been a unitary response to the loss of the

lake.

Figure 6.4 The ethnographic distribution of linguistic

groups in the region around Lake Cahuilla.

Effects on Resources

The most critical issue in evaluating possible regional repercussions

of Lake Cahuilla's changing levels concerns the lake's effects on the

availability of subsistence resources. The matter has sometimes been framed

as a debate between the Weide and Wilke models for settlement and adaptation

to the lake. According to the Weide Model, because of the instability

of the lake, lacustrine resources were relatively unreliable and sporadically

distributed, settlement on the lakeshore was only seasonal, and reliance

on the lake was no more than a secondary element within regional adaptive

strategies (Schaefer 1994; M. Weide 1976). On the other hand, according

to the Wilke Model, lake resources were extensively used, lakeshore settlement

was nearly year-round, and therefore, the loss of resources carried great

regional consequences (Wilke 1978).

Lake Cahuilla's appearance within its basin must have been a strongly

positive development from the standpoint of the resources provided. It

is true that the areas flooded by the lake were presumably used by native

peoples during dry periods, but such use was probably of minor importance,

as was the case for the portions of the Imperial and Coachella valleys

lying below the maximum shoreline in the subsistence strategies of later,

ethnographically known groups. Mesquite was a significant resource, and

the rise of the lake may have reduced the total regional mesquite crop.

Salt may have been harvested from the lake’s dry playa, although

it was of lesser importance. The obsidian deposits at Obsidian Butte became

unavailable once the lake had risen above the level of 40 meters below

sea level. When obsidian from this source was available, it was collected,

used locally, and traded or carried westward to coastal southern California,

but it appears unlikely that it had any major economic importance.

New resources made available by the lake would have more than offset the

losses mentioned above. Archaeological evidence suggests the harvesting

and consumption of fish, shellfish, waterfowl, and marsh plants at lakeshore

sites (e.g., Laylander 1997a:86-90; Sutton and Wilke 1988; Wilke 1978).

Although the economic value of these resources is not easy to quantify,

it likely far exceeded the local losses in mesquite and other dry-phase

resources. The availability of potable water was another critical resource

for human survival in the hot, arid Colorado Desert. The water of the

lake and the high water table near its shores probably supported richer

populations of non-lacustrine plants and animals than would otherwise

have been present. Those augmented populations, in turn, became available

for human exploitation.

If the rise of the lake substantially enhanced the resources of the Coachella

and Imperial valleys, a different situation existed farther south in the

Colorado River's delta. As documented ethnohistorically and ethnographically,

the delta was a rich environment for human settlement. Wild rice, quelite,

fish, and water birds were major natural food resources, along with numerous

minor ones. The delta also allowed for floodwater agriculture (Castetter

and Bell 1951; Kelly 1977). However, when the river's flow diverted north

into the Lake Cahuilla Basin, the diversion was substantially total, the

making the delta unattractive to humans for a period lasting nearly two

decades. After the basin filled, the river would have once again sent

part of its water, perhaps amounting to about half of its total flow,

into the delta by way of the lake’s outlet. This would have made

the delta inhabitable, although perhaps with a proportionately lower share

of resources than under non-lacustrine conditions. When the river diverted

its full flow directly to the delta once again, that environment was gradually

enriched while the isolated lake to the north receded. Resource conditions

in the delta and in the Lake Cahuilla basin were thus to some extent complementary,

perhaps triggering a synchronization of prehistoric human responses.

Regional Ethnographic and Archaeological Patterns

The Spread of Technology

One of the earliest archaeological suggestions for a regional effect from

the inundation and recession of Lake Cahuilla was the spread of a ceramics

industry westward, first from the lower Colorado River into the Lake Cahuilla

basin and then from the basin to the mountains and coast of southern California

and northern Baja California. Malcolm J. Rogers thought that the lake

rose around AD 1000, at which time Yuman-speaking people had carried pottery-making

from the lower Colorado River into the Lake Cahuilla basin (1939, 1945).

When the lake had receded around AD 1500, according to Rogers, ceramics

passed to the Peninsular Range and the Pacific coast.

Rogers' model for the spread of ceramics is no longer compelling, as it

is now believed that there were several shorter lake stands rather than

a single long one, and those stands took place both prior to AD 1000 and

after AD 1500. Pottery was likely manufactured and used earlier than Rogers

thought, both within the Lake Cahuilla basin and in the Peninsular Range

(Griset 1996; Waters 1982). Certain current hypotheses assert that ceramic

technology in the western areas developed to a large extent independently,

rather than being copied from the east (Griset 1996).

A link between the spread of ceramic technology and ethnic migration also

seems less convincing now than it did when Rogers wrote. Archaeological,

early historic, and ethnographic evidence makes it clear that west coast

groups were in close contact with the peoples who lived beside the lower

Colorado River. The westerners would therefore have had access to the

technological ideas required for pottery production. What was critical

for the spread of ceramic technology was not access to information about

how to make pottery, but rather the proper economic incentives and circumstances,

such as a fair degree of sedentism that would have made pottery an attractive

alternative to other types of containers. These factors can only be indirectly

linked to the cycles of Lake Cahuilla.

The Distribution of Languages

Traces left by the cyclical appearance and disappearance of Lake Cahuilla

may exist in the region’s map of aboriginal languages. In principle,

a region that had experienced long-term territorial stability would be

expected to contain a mosaic of optimally sized linguistic communities

that were only remotely related to each other (cf. Dixon 1997). In contrast,

regions that had experienced very recent ethnic expansions or migrations

by some groups at the expense of others might be recognized by the presence

of single-language communities with dialect-level variation spread across

areas that would have been too extensive for linguistic unity to have

been maintained over the long term. If such expansions or migrations had

occurred less recently, the resulting pattern in linguistic geography

might be an array of sister-languages belonging to an easily recognized

linguistic family. If Lake Cahuilla's resources played an important role

in supporting elevated population levels within its basin, then the loss

of those resources when the lake dried up may have stimulated migrations

at the expense of neighboring groups. With time, migrant groups may have

become linguistically differentiated from their kin who either had not

migrated or had moved in other directions. There are several linguistic

patterns in the region that may reflect repercussions from the lake's

late prehistoric cycles.

Speakers of Yuman languages occupied areas to the south and east of the

Lake Cahuilla basin. Yuman is one of at least 13 linguistic families that

are mostly scattered around the periphery of California and that seem

to have been distantly related to each other within the Hokan phylum.

Yuman was by far the most extensive of the Hokan families; it had the

largest number of member-languages, and it probably also had the largest

number of pre-contact speakers. This distinctiveness in territorial and

demographic size and in diversity is further enhanced if Yuman’s

closely related sister family, Cochimí, which adjoined Yuman to

the south in central Baja California, is taken into consideration (Mixco

1978). The geographical extent of the Yuman family suggests that a substantial

territorial expansion had taken place at some time during the second half

of the Holocene.

The available methods for dating the separations between languages are

imprecise at best. Glottochronology offers an approach to linguistic dating

that is comparatively objective, although its validity has been seriously

challenged by many linguists. For what it may be worth, a glottochronological

estimate has put the separation of Yuman into its four major branches–River,

Delta-California, Pai, and Kiliwa–at about 1,700-2,500 years ago

(Laylander 1997b:66; cf. Ochoa 1982; Robles 1965). This suggests that

the formation of these branches predated the late prehistoric period,

and was prior to at least the three most recent stands of Lake Cahuilla.

However, the division of the three northern Yuman branches (Delta-California,

River, and Pai) into their constituent languages brings this discussion

closer to the period when something is more securely known about the status

of Lake Cahuilla.

Delta-California Yuman includes a minimum of two languages, Cocopa and

Diegueño, and a maximum of eight languages, if a separate status

is accorded to Cocopa, Kahwan, Halyikwamai, Ipai, Kumeyaay, Tipai, Huerteño,

and Kwatl. Glottochronology suggests that there was a separation of 1,200

years or less within this branch of the Yuman family. The ethnographically

recorded location of the Delta-California Yumans both on the southwestern

and southern margins of the former lake and to the west of the lake basin

would fit with the hypothesis that outward expansion toward the west and

south may have been triggered by one or more of the lake's episodes of

desiccation.

Accounts of the Colorado River’s delta by early Spanish visitors

identified the presence there of several groups, including those generally

known subsequently as the Cocopa, Kahwan, and Halyikwamai. In the early

nineteenth century, the Kahwan and Halyikwamai moved out of the delta

to the middle Gila River, where they joined with River Yumans, the Maricopa.

Linguistic evidence concerning the Kahwan and Halyikwamai is very limited,

but what little evidence is available suggests that their speech may have

been essentially identical to that of the Cocopa (Kroeber 1943:21-22).

The three delta groups may have been primarily sociopolitical rather than

cultural-linguistic groupings, but it is noteworthy that their recognition

as distinct entities persisted through more than three centuries of the

protohistoric period. This suggests that the Yumans living in the delta

were in an early stage of cultural fission into three ethnolinguistic

units, reflecting a process of differentiation that had begun less than

1,000 years ago, perhaps only a very few centuries prior to contact. Such

a fission could be connected to some territorial expansion occurring as

part of one of the late prehistoric cycles of Lake Cahuilla.

Scholars disagree as to the amount of linguistic differentiation present

within Diegueño, or Kumeyaay. Some interpretations suggest that

only a single language is represented, while lexicostatistical evidence

seems to hint at as many as five separate but closely related languages.

Currently, the most widely accepted interpretation is that there are three

distinct languages: Ipai in the north, Kumeyaay in the center and east,

and Tipai in the south (Goddard 1996; Kendall 1983; Langdon 1990). This

would suggest that linguistic fission was triggered within this group,

perhaps about 1,200-1,000 years ago, with the possibility of some more

recent, dialect-level breaks as well.

The distribution of the River Yuman languages offers fewer hints of repercussions

from Lake Cahuilla. The Halchidhoma were recorded in the Colorado delta

in 1605, prior to the lake’s final stand, but they had relocated

themselves farther north, near Blythe, when they were next heard from

in the eighteenth century. They then moved to the middle Gila to join

the Maricopa in the early nineteenth century (e.g., Laylander 2004b).

One scenario suggests that the Maricopa may have ventured from the lower

Colorado River to the Middle Gila in the thirteenth century, a move that

might have been associated with a lake cycle (Harwell and Kelly 1983:73;

Spier 1933:11-12).

At first sight, the Pai branch of Yuman seems remote from Lake Cahuilla.

There are two Pai languages: Paipai in northern Baja California, and Upland

Yuman in northwestern Arizona. The latter is commonly divided into the

sociocultural groupings of the Yavapai, Walapai, and Havasupai. Neither

of the Pai languages was spoken within or adjacent to the Lake Cahuilla

basin. However, it is striking that the areas in which the two languages

were spoken were not contiguous, as were the territories of sister-languages

within the other Yuman branches, but instead were separated by a gap of

about 200 km. The midpoint between the territories of the Pai languages

falls within the Colorado River delta. There is no accepted estimate as

to how long ago Paipai and Upland Yuman became separated from each other,

but the relationship between the languages is a close one. Perhaps 1,200-1,000

years would once again be a reasonable guess, although some scholars would

see the relationship as much closer (cf. Winter 1967). The direction of

migration is uncertain. Some modern oral traditions seem to point toward

a movement of the ancestral Paipai from western Arizona to Baja California

(e.g., Meigs 1977; Mixco 1977; Wilken 1993; Winter 1967), while linguistic

indications seem to favor movement in the reverse direction (Joël

1998; Laylander 1997b). Migration of both groups from a third location

is also a possibility. In any case, some dramatic event during the late

prehistoric period seems necessary to account for the geographic separation

of the two languages. A cycle of Lake Cahuilla is one candidate.

The geographical extent of the area occupied by the Upland Yuman language

and the fission of its speakers into three culturally distinct and sometimes

hostile ethnic groups (the Yavapai, Walapai, and Havasupai) also calls

for comment. The territory occupied by Upland Yuman speakers amounted

to about 100,000 km2, perhaps more land than could be maintained indefinitely

as a single language unit. The sociopolitical fission into Yavapai, Walapai,

and Havasupai is a likely result of this proposed instability. If that

inference is correct, the expansion of the Upland Yumans through much

of western Arizona must have been a relatively recent phenomenon, begun

less than 1,000 years ago. Ethnic displacements from the Lake Cahuilla

basin or from the Colorado delta are possible as either direct or indirect

catalysts for the Upland Yuman expansion.

The distribution of the Takic (Uto-Aztecan) languages offers fewer hints

at possible effects from the late prehistoric lake. A noted feature of

aboriginal southern California’s linguistic geography was the "Shoshonean

Wedge." Speakers of Takic languages occupied the coastline between

Malibu and Carlsbad, separating two Hokan-speaking families, the Yumans

to the south and the Chumash to the northwest. However, the relationship

between Yuman and Chumash languages is at best an extremely remote one,

perhaps dating back to the early Holocene. Additionally, a study of borrowed

words within the basic vocabularies of the coastal Takic languages, Gabrielino

and Luiseño, suggests that those groups displaced or absorbed the

speakers of a previous coastal language or languages that were distinct

from both Yuman and Chumash (Bright 1976; Laylander 1985). The major linguistic

fissions within Takic, and therefore the territorial expansions that probably

produced them, all appear to predate the late prehistoric period. Glottochronology

suggests that (1) Takic became differentiated from the other northern

Uto-Aztecan branches around 3,000-4,000 years ago; (2) Takic divided into

Cupan and Serrano-Gabrielino around 2,500 years ago; and (3) Cupan split

into Luiseño, Cupeño, and Cahuilla more than 2,000 years

ago. The expansion of Takic speakers to the southern California coast,

forming the Shoshonean Wedge, would most plausibly be associated with

either the first or the second of those linguistic fissions.

One feature of Takic linguistic geography perhaps related to late prehistoric

Lake Cahuilla is the dialect-level distinction between Mountain, Pass,

and Desert Cahuilla (Seiler 1977:6-7). The time depth of this division

is unclear, although estimated at 1,000 years ago, assuming that it reflected

linguistic instability that was gradually leading toward a language-level

split. It is possible that the cultural differentiation of these three

subgroups reflects an episode of ethnic expansion, either eastward from

the Peninsular Range to the shore of Lake Cahuilla, or westward into the

mountains, away from the drying lake basin. However, the dialects might

merely reflect stable variability within the language, and that their

centrifugal tendencies from local change were completely balanced by centripetal

tendencies to maintain mutual intelligibility throughout Cahuilla territory.

Demography

Many of the suggested regional repercussions from Lake Cahuilla are related

to a demographic disequilibrium associated with abrupt changes in the

basin's carrying capacity. Groups that were displaced from the basin or

from the Colorado delta may have raised the population densities within

surrounding areas, either temporarily or permanently.

The size of the region's late prehistoric and protohistoric population

is difficult to determine. It is not uncommon for ethnographic estimates

of pre-contact populations to vary by a factor of two, and sometimes by

as much as a factor of five (e.g., Heizer 1978; Hicks 1963; Kroeber 1925;

Shipek 1986; White 1963). Estimation of regional populations by means

of archaeological evidence has not been seriously attempted, and such

a project would face daunting difficulties. If the population of the surrounding

region is known only roughly, the situation within the basin when Lake

Cahuilla was present is also uncertain. Homer Aschmann gave a range for

population estimates between 20,000 and 100,000 for the basin (1959:45).

The latter figure certainly seems too high, and even the former may well

be excessive, but there is no good basis at present for a sounder estimate.

Aschmann postulated a "great migration" of people faced with

starvation, resulting in "an extraordinarily vicious war pattern"

on the Colorado River but "some sort of peaceful accommodation of

an enormous influx of former desert dwellers" by coastal groups to

the west (1959:45). James F. O'Connell (1971) and Wilke (1974) similarly

suggested that significant population increases had occurred in the surrounding

areas as a result of migrations out of the former lake's basin.

It is reasonable to ask whether the relative density of the late prehistoric

and protohistoric population in the region was greater than might have

been expected in the absence of the Lake Cahuilla phenomenon. According

to estimates by Frederic N. Hicks, the aboriginal population densities

for the groups living along the Colorado River ranged between 2.0 and

3.4 people per km2, and the densities in the deserts, mountains, and coastal

plains to the west of the river ranged from 0.15 to 1.0 people per km2

(1963). The dense settlement along the river is plausibly associated with

the practice of floodplain agriculture there, but the question remains

open: was the population density so high because agriculture was practiced,

or was agriculture practiced because the population density was high?

The population sizes among the western groups are also notably large if

viewed within a worldwide perspective (Kelly 1995:222-226). However, that

was true for native California in general, in a zone extending well beyond

the range of any likely effects from the lake.

Subsistence Strategies

Anomalies in the use of non-lacustrine subsistence resources are another

set of possible symptoms for regional changes associated with Lake Cahuilla.

Among the processes stimulated by environmental instability may have been

a more intensive exploitation of some previously used resources, the addition

of new and presumably lower-ranked resources, maintenance of a diversified

resource strategy as a hedge against that instability, and relaxation

of cultural mechanisms promoting sustainability in resource exploitation.

The phases of the lake that involved the wholesale disappearance of lacustrine

or deltaic plants and animals may have seriously affected the total quantities

of the preferred subsistence resources that were available within the

region. If so, perhaps that compensation would have been sought in the

adoption of less attractive, higher-cost subsistence strategies. Such

subsistence changes might also have occurred as the result of technological

advances or population increases that were unrelated to environmental

change. The detailed analyses that might make it possible to distinguish

among these various causes behind subsistence change have generally not

been performed. However, it is worthwhile to examine what was distinctive

about late prehistoric subsistence practices in the region and to consider

Lake Cahuilla as at least one potential explanation.

Agriculture was the most striking late prehistoric innovation in subsistence.

The Yumans on the Colorado River were growing crops when the Spanish encountered

them in 1540. It is likely that local agriculture predated that event

by several centuries, although the timing of its introduction is yet unknown.

Among the peoples of the river and the delta, ethnographic records show

that agricultural crops constituted an important, but not a dominant,

food source. Estimates of the dietary contribution from agriculture range

between a high of 40-50% among the Mohave to about 30% for the Cocopa

(Castetter and Bell 1951). Some Kumeyaay (Kamia) lived with the Quechan

on the Colorado River in early historic times, where they presumably practiced

agriculture. The eastern Kumeyaay also planted crops in the parts of the

Imperial Valley that were watered by natural overflow from the Colorado

River (Gifford 1931). Whether the Cahuilla of the Coachella Valley practiced

agriculture prior to the advent of European influences is disputed (Bean

and Lawton 1973; Lawton 1974; Schaefer and Huckleberry 1995; Wilke et

al. 1977). It has been suggested that the prehistoric Yuman and Takic

groups in the Peninsular Range and on the Pacific coast may have engaged

in agriculture to a significant extent (Bean and Lawton 1973: Forbes 1963;

Shipek 1986, 1993), but this view has also been challenged (e.g., Laylander

1995).

One explanation for the advent of agriculture late within the prehistoric

period is that the domesticated crop plants (primarily maize, tepary beans,

and squashes or pumpkins), as well as the techniques for their cultivation,

only became available after they spread from their centers of development

elsewhere in parts of North America. An alternative view would be that

the cultigens and techniques were potentially available at an earlier

time, but that the added labor costs involved in their exploitation were

only bearable after the regional population had risen to a level that

could no longer be supported by less costly methods of subsistence. Such

population-related subsistence stress might have been related to any of

several causes: a gradual growth of population acting as an essentially

independent variable through time; a spurt of population growth induced

by social factors, such as interethnic military competition; or episodic

population displacement and subsistence stress relating to environmental

perturbations, such as those arising from the cycles of Lake Cahuilla.

Future studies may be able to date the introduction of agriculture more

accurately, establish its pre-contact geographical range, evaluate its

relative costs and benefits under aboriginal conditions, and clarify the

possible role of Lake Cahuilla in its adoption.

A striking feature of late prehistoric subsistence in the Peninsular Range

and the coastal valleys west of the Lake Cahuilla basin was the prime

importance attributed to acorn harvesting. Archaeological site frequencies

suggest that the occupation of these parts of the region became much more

intensive during the late period than it had been during earlier times

(e.g., Christenson 1990). There was a significant later proliferation

of bedrock milling features primarily associated with acorn processing.

Ethnographic evidence indicates that acorns were the single most important

subsistence resource for the western Kumeyaay, Luiseño, Cupeño,

and western Cahuilla. It is conceivable, but not very likely, that the

late florescence of acorn use was induced by a technological innovation:

the discovery of how to leach acorns to make them edible. More probably,

late peoples had known of the potential but turned to the region's abundant

acorns only when other resources that were less costly to process were

no longer sufficient to feed a growing population. A similar late prehistoric

rise in acorn use, probably associated with rising population density,

is reported throughout much of California, far beyond the zone that can

plausibly be connected with Lake Cahuilla (e.g., Basgall 1987). Late prehistoric

demographic growth in the southwestern part of California may also have

been unrelated to events in the Lake Cahuilla basin, but it is possible

that the displacements associated with the lake played a role in inducing

subsistence stress and in stimulating the local development of an acorn-based

economy.

Agave was another resource of key importance, particularly among the people

who lived along the eastern margins of the Peninsular Range, including

the Cahuilla, eastern Kumeyaay, and Paipai. For some of these groups,

ethnographic evidence indicates that agave was the primary subsistence

resource, taking over the role that was being played by acorns farther

west. Agave hearts or stalks were processed by roasting in large, usually

rock-lined pits; the archaeological remains of thousands of these features

dot the eastern margins of the Peninsular Range. Some limited radiocarbon

sampling of roasting pits in southeastern San Diego County suggests that

the features primarily postdate AD 1350, and M. Steven Shackley (1983,

1984) posited a correlation between the florescence of pit roasting and

the recession of Lake Cahuilla. As in the case of acorns, an upsurge of

agave processing may have been part of a pattern of regional subsistence

intensification linked to population growth. The possibility that it was

specifically related to groups that had been displaced from the western

shores of Lake Cahuilla merits further consideration.

Pine nuts were a resource with a somewhat more limited distribution, but

they played an important role in some parts of the Peninsular Range. The

chronology of local pinyon exploitation is unknown. Given the evident

upsurge of settlement in the mountains during the late prehistoric period

(e.g., Graham 1981; True 1970), it would not be unreasonable to suggest

that nuts were part of an intensified regional subsistence strategy, although

the evidence to confirm or refute this suggestion is presently lacking.

In addition to adopting the use of new subsistence resources or intensifying

the use of old ones, the region's cultures may have responded to environmental

instability through changes in their general approaches to resource use.

One such response might have been toward diversification, or generalization.

Perhaps particular resources were cyclically made available but were then

lost because of the changes occurring in the lake basin and the delta.

If so, it may have been important for the prehistoric inhabitants of the

region to maintain their familiarity with the procurement and use of a

wider range of potential substitute resources than would have been necessary

under more stable environmental conditions. Several ethnographers argued

that the peoples living along the lower Colorado River made use of that

region's subsistence potential in a manner that was less than optimal

(e.g., Castetter and Bell 1951:68-72; Kelly 1977:23). Some early historic

observers attributed this to "laziness" (Bolton 1930:4:108;

Hammond and Rey 1953:1017). Such a failure to optimize, which was being

criticized from a synchronic perspective, may have made good sense diachronically,

as a defense against the effects of recurrent environmental changes.

Even more speculatively, another response to dramatic environmental change

may have been for people in and around the Lake Cahuilla basin to relax

prevailing cultural mechanisms for sustainability in the ways they exploited

particular resources. Sustainability in subsistence practices has been

attributed to many hunter-gatherer cultures, although this may possibly

be a modern environmentalist twist on the “noble savage” myth.

Substantial evidence for the existence of any cultural mechanisms to enforce

such a pattern is often lacking. Assuming that mechanisms protecting sustainability

and preventing overexploitation of resources did commonly exist, they

might have been suppressed in areas such as the Lake Cahuilla basin and

the Colorado River delta. Experience in those areas would have indicated

that resources that were not fully used would be lost to the recurrent

environmental disasters.

Trade

Intra- and interregional exchange systems offered a potential mechanism

for buffering the effects of environmental instability in the Lake Cahuilla

basin and the Colorado delta. Exported goods may have been directly traded

for subsistence resources in periods of stress. The social links that

were created through exchange may also have served to create places of

refuge for displaced persons, or allies for those involved in conflict.

Archaeological, historical, and ethnographic evidence attests to the existence

of trade networks linking the Pacific coast with the Colorado River valley

and parts of the American Southwest still farther east, as well as to

north-south connections between the Gulf of California and the Great Basin

(e.g., Bennyhoff and Hughes 1987; Davis 1961). The most archaeologically

visible elements of trade, such as pottery and shell ornaments, were items

that do not directly reflect subsistence. This may indicate that the establishment

of social ties between individuals and communities was more important

than strictly economic complementarity, but it is also possible that the

surviving material record is misleading in this respect.

Early historic accounts attest to visits made by Mohave and Halchidhoma

travelers to the southern California coast (Forbes 1965:61-62). Such trips

had to cover distances of more than 400 km, crossing several ethnic boundaries.

Direct trade on this geographical scale was unusual in aboriginal California,

and its existence here may point to a heightened emphasis on exchange

within the southern part of the state.

The westward movement of obsidian from the Obsidian Butte source on the

bed of Lake Cahuilla is another suggestive pattern. The movement of this

material, whether in trade or through direct procurement, was greatly

enhanced during the latest part of the late prehistoric period. Evidence

for this comes from the increased frequency of obsidian specimens in late

sites in montane and coastal southern California and from the regional

distribution of hydration values. The upsurge in obsidian use may have

been part of a general pattern of enhanced trade, or it may have been

a specific mechanism for extracting economic value from labor within the

dry Lake Cahuilla basin. Alternatively, it may merely indicate that the

obsidian source area had not usually been accessible during earlier periods,

because it was submerged whenever the lake waters stood 40 m below sea

level.

Settlement and Social Organization

Another symptom of environmental instability may be the social organization

of communities in the region surrounding the Lake Cahuilla basin. All

of the ethnographically documented peoples of the region possessed patrilineal

descent groups. In the case of the Takic-speaking Cahuilla, Serrano, and

Luiseño, these patriclans were localized in particular communities

(Heizer 1978; Strong 1929). It may be hypothesized that this Takic model

for social organization was the region's basic pattern, and that deviations

from it arose as a result of specific causes, which may have included

an influx of people displaced by environmental change.

Among the Yumans living on the Colorado River and in its delta, the patriclans

were rather weak spatially intermixed units. Settlement was usually dispersed

into scattered homesteads and hamlets, rather than being nucleated in

villages. Hicks (1974) plausibly attributed this settlement pattern to

the exigencies of floodplain agriculture, which required that families

live close to their fields and change their residences from time to time

as the flooding river shifted its course. It is also possible that population

shifts into and out from the river valley as a result of the lake cycles

contributed to this breakdown in the importance and localization of patriclans.

The social and settlement organization of the western Yumans, including

the Kumeyaay and Paipai, are less clearly defined (Laylander 1991). Most

early twentieth century ethnographers reported essentially clan-based

settlements similar to those of the Takic groups, although a few later

analysts have suggested an institutionalized dispersion of the clans into

multi-clan settlements (e.g., Shipek 1982). Most of the authoritative

accounts also indicated that whereas there was a strong tendency toward

clan localization as a cultural ideal, in practice the settlements commonly

contained representatives from more than one clan. Furthermore, a particular

clan was likely to be represented at more than one settlement. If this

system is interpreted as a partial breakdown of an underlying Takic settlement

model, then recent disruptions as a result of the influx of outside population

from the basin or delta could help to explain the deviations.

Warfare and Political Organization

Another symptom of social instability potentially induced or aggravated

by the environmental instability associated with Lake Cahuilla was the

exceptional importance and scale of intercommunity violence on the lower

Colorado and Gila rivers. If the appearance and disappearance of Lake

Cahuilla caused significant dislocations for people within the region,

one outcome of those dislocations may have been conflicts over territories

lying outside of the lake basin. Even if conflicts were not rationalized

by the participants as territorial struggles, they might have arisen from

and dealt with the interethnic stresses resulting from serious losses

in regional resources.

The contrast between patterns of warfare in most of California and those

followed along the lower Colorado River is striking. Native Californian

cultures have sometimes been characterized as essentially pacific, although

this is valid only in a relative sense, or if the category of warfare

is limited to specific types of intercommunity violence that are characterized

by elevated numbers of combatants and casualties, tactical organization,

or persistence. For example, Joseph G. Jorgensen (1980:240) defined warfare,

as distinct from raiding, as "a political act engaged in by two groups,

each possessing definite leadership, military tactics, and the expectation

that a series of battles could be endured." In his survey of ethnographic

information on aboriginal cultures throughout western North America, Jorgensen

identified only two areas where warfare in this restricted sense was practiced:

among the Tsimshian of coastal British Columbia, and among the River Yumans.

Colorado River warfare appears to have commonly involved unusually large

political units—whole ethnolinguistic groups, or collaborative ethnolinguistic

groups with longstanding alliances. Of note were a system of two adversarial

alliances centered on the Mohave and Quechan on one side and on the other

their enemies, the Cocopa and Maricopa. According to Jorgensen's survey,

district-level political organization, with units encompassing multiple

villages, was relatively rare in western North America. However, this

organization was reported for the Nisenan, Salinan, Chumash, and River

Yumans. In the case of the River Yumans, the functions and authority of

district-level (tribal) leaders were almost exclusively military, rather

than economic, judicial, or ceremonial.

Warfare was also deeply imprinted in the ceremonial behavior of the Colorado

River groups. In the case of the Mohave, for example, this was evidenced

in the formal, named social roles associated with warfare, including braves

(clubbers), spies, scalpers, scalp custodians, and female scalp dancers;

elaborate ceremonial behavior, including pre-combat conferences, anticipatory

funeral singing, observation of omens, and post-combat victory ceremonies

(notably the scalp dance); a special place in the afterlife reserved for

braves or men killed in battle; and the exceptional prominence accorded

to accounts of warfare in traditional narratives (Fathauer 1954; Kroeber

1948, 1951, 1972).

A variety of different interpretations have been offered as to why the

Colorado River cultures assigned an unusually large role to military matters.

Some analysts see the pattern as primarily protohistoric, attributable

to European disruptions and the incentives of raiding for slaves and horses

(e.g., Dobyns et al. 1957). However, the pervasiveness of militarism in

the Colorado River cultures seems to suggest a longer-established phenomenon.

Early historic accounts strongly suggest that chronic warfare was already

present at the period of initial contact prior to any substantial European

influences, although effects emanating from the frontier of European control

may later have reinforced this tendency.

Some of the explanations offered to account for Yuman militarism are essentially

ideological. For example, George H. Fathauer (1954:114) argued that economic

or material reasons for Mohave warfare were unimportant, at least once

the Mohave were established in their traditional homeland, and that their

observed bellicosity was essentially “an expression of their nationalistic

religious philosophy.” Viewed from an essentially emic or synchronic

perspective, Fathauer's argument has considerable support. Yuman warfare

was often conducted far from the aggressors' own territories, typically

entailed little or no attempt to seize crops or possessions or to occupy

conquered land, and participants' accounts of their own motivations emphasized

factors such as the pursuit of prestige or revenge rather than material

gain. On the other hand, if there was indeed an ethos among these groups

that accounted for the persistence of chronic warfare without immediate

material objectives, the question remains as to how this unusual ethos

originated. Is it necessary to dismiss it simply as an aberration arising

from the hazards of random cultural mutation? Or were there unusual material

circumstances that motivated the creation of such an ethos?

Economic explanations for Colorado River warfare include those offered

by Chris White (1974), Albert H. Schroeder (1981), and Connie L. Stone

(1981). White argued that warfare and the system of ethnic alliances associated

with it served to alleviate periodic subsistence stress. Stone similarly

suggested that River Yuman warfare was a response to frequent food shortages.

Food theft was a definite feature of some raiding, and disputes over mesquite

gathering rights and prime agricultural lands may have functioned as a

casus belli. Schroeder proposed that trading was a key factor in Colorado

River warfare, arising from a need to protect trade lanes and from competition

between rival trading centers.

If Colorado River warfare was generally not formulated emically as a struggle

for control over territories or resources, its most prominent consequences,

viewed etically, seem to have been territorial. First the Maricopa and

Kavelcadom, and subsequently the Halchidhoma, Kahwan, and Halyikwamai,

left the lower Colorado River and migrated to the middle Gila River, where

they became culturally consolidated as Maricopa (Spier 1933). Early historic

accounts also mention the presence of other unnamed or presently unidentifiable

groups living on the Colorado River, and it is possible that additional

ethnic migrations, assimilations, or extinctions may have occurred during

the protohistoric centuries. Regional environmental instability offers

an attractive explanation for such displacements and for the pattern of

exaggerated interethnic violence associated with them.

Conclusions

Plausible links have been suggested, although not firmly established, between Lake Cahuilla and such diverse elements as the distribution of languages and dialects within the region, tendencies toward subsistence intensification, and a focus on interethnic warfare. To advance the discussion of these issues, two main lines of evidence and argument need to be pursued. One is to continue refining our understanding of the prehistoric chronology, resource use, and settlement systems directly associated with the lake. The second is to evaluate critically the regional patterns proposed as consequences of the lake cycles, both to confirm their reality as empirical phenomena and to compare the ability of competing explanations to account for them. Clearly, a monocausal interpretation of the later prehistory and ethnography of southern California, northern Baja California, and western Arizona, with Lake Cahuilla playing the role of a prime mover, is not warranted by the evidence. On the other hand, to neglect the dramatic environmental changes associated with the lake as a potentially important factor in prehistoric changes and in ethnographic cultural patterns would be a serious mistake.

References Cited

Aschmann, Homer

1959 The Evolution of a Wild Landscape and Its Persistence in Southern

California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 49(3):34-57.

Basgall, Mark E.

1987 Resource Intensification among Hunter-Gatherers: Acorn Economies

in Prehistoric California. Research in Economic Anthropology 9:21-52.

Bean, Lowell John, and Harry W. Lawton

1973 Some Explanations for the Rise of Cultural Complexity in Native California

with Comments on Proto-Agriculture and Agriculture. In Patterns of Indian

Burning in California: Ecology and Ethnohistory, by Henry T. Lewis, pp.

v-xlvii. Ballena Press, Ramona, California.

Bennyhoff, James A., and Richard E. Hughes

1987 Shell Bead and Ornament Exchange Networks between California and

the Western Great Basin. American Museum of Natural History Anthropological

Papers 64:79-175. New York.

Bolton, Herbert E.

1930 Anza's California Expeditions. 5 vols. University of California Press,

Berkeley.

Bright, William

1976 Variation and Change in Language. Stanford University Press, Stanford,

California.

Castetter, Edward F., and Willis H. Bell

1951 Yuman Indian Agriculture: Primitive Subsistence on the Lower Colorado

and Gila Rivers. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Christenson, Lynne E.

1990 The Late Prehistoric Yuman People of San Diego County, California:

Their Settlement and Subsistence System. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University, Tempe.

Davis, James T.

1961 Trade Routes and Economic Exchange among the Indians of California.

University of California Archaeological Survey Reports No. 54. Berkeley.

Dixon, Robert M. W.

1997 The Rise and Fall of Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

U.K.

Dobyns, Henry F., Paul H. Ezell, Alden W. Jones, and Greta S. Ezell

1957 Thematic Changes in Yuman Warfare. In Cultural Stability and Cultural

Change, edited by Verne F. Ray, pp. 46-71. American Ethnological Society,

Seattle.

Fathauer, George H.

1954 The Structure and Causation of Mohave Warfare. Southwestern Journal

of Anthropology 10:97-118.

Forbes, Jack D.

1963 Indian Horticulture West and Northwest of the Colorado River. Journal

of the West 2:1-14.

1965 Warriors of the Colorado: The Yumas of the Quechan Nation and Their Neighbors. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Gifford, E. W.

1931 The Kamia of the Imperial Valley. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin

No. 97. Washington, D.C.

Goddard, Ives

1996 Introduction. In Languages, edited by Ives Goddard, pp. 1-16. Handbook

of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant, general editor, vol.

17. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Graham, William R.

1981 A Cultural Resource Survey of the Laguna Mountain Recreation Area,

San Diego County, California. Archaeological Systems Management, San Diego.

Griset, Suzanne

1996 Southern California Brown Ware. Ph.D. dissertation, University of

California, Davis.

Hammond, George P., and Agapito Rey

1953 Don Juan de Oñate, Colonizer of New Mexico. University of

New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Harwell, Henry O., and Marsha C. S. Kelly

1983 Maricopa. In Southwest, edited by Alfonso Ortiz, pp. 71-85. Handbook

of North American Indians, Vol. 10, William C. Sturtevant, general editor,

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Heizer, Robert F. (editor)

1978 California. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8, William C.

Sturtevant, general editor, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Hicks, Frederic N.

1963 Ecological Aspects of Aboriginal Culture in the Western Yuman Area.

Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles. University

Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

1974 The Influence of Agriculture on Aboriginal Socio-Political Organization in the Lower Colorado River Valley. Journal of California Anthropology 1:133-144.

Joël, Judith

1998 Another Look at the Paipai-Arizona Pai Divergence. In Studies in

American Indian Languages: Description and Theory, edited by Leanne Hinton

and Pamela Munro, pp. 32-40. University of California Publications in

Linguistics No. 131. Berkeley.

Jorgensen, Joseph G.

1980 Western Indians: Comparative Environments, Languages, and Cultures

of 172 Western American Indian Tribes. W. H. Freeman, San Francisco.

Kelly, Robert L.

1995 The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways. Smithsonian

Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Kelly, William H.

1977 Cocopa Ethnography. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona

No. 29. Tucson.

Kendall, Martha B.

1983 Yuman Languages. In Southwest, edited by Alfonso Ortiz, pp. 4-12.

Handbook of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant, general editor,

vol. 10. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Kroeber, A. L.

1925 Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology

Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

1943 Classification of the Yuman Languages. University of California Publications in Linguistics 1:21-40. Berkeley.

1948 Seven Mohave Myths. University of California Anthropological Records 11:1-70. Berkeley.

1951 A Mohave Historical Epic. University of California Anthropological Records 11:71-176. Berkeley.

1972 More Mohave Myths. University of California Anthropological Records 27:1-160. Berkeley.

Langdon, Margaret

1990 Diegueño: How Many Languages? In Papers from the 1990 Hokan-Penutian

Languages Workshop Held at University of California, San Diego, June 22-23,

1990, edited by James E. Redden, pp. 184-190. Occasional Papers on Linguistics

No. 15. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Lawton, Harry W.

1974 Agricultural Motifs in Southern California Indian Mythology. Journal

of California Anthropology 1:52-79.

Laylander, Don

1985 Some Linguistic Approaches to Southern California's Prehistory. San

Diego State University Cultural Resource Management Center Casual Papers

2(1):14-58.

1991 Organización comunitaria de los yumanos occidentales: una revisión etnográfica y prospecto arqueológico. Estudios Fronterizos 24/25:31-60.

1995 The Question of Prehistoric Agriculture among the Western Yumans. Estudios Fronterizos 35/36:187-203.

1997a The Last Days of Lake Cahuilla: The Elmore Site. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 33(1/2):1-138.

1997b The Linguistic Prehistory of Baja California. In Contributions

to the Linguistic Prehistory of Central and Baja California, edited by

Gary S. Breschini and Trudy Haversat, pp. 1-94. Coyote Press Archives

of California Prehistory 44. Salinas, California.

2004a Remembering Lake Cahuilla. In Proceeding of the Millennium Conference: The Human Journey & Ancient Life in California’s Deserts, edited by Mark Allen and Judyth Reed, pp. 167-171. Maturango Press, Ridgecrest, California.

2004b Geographies of Fact and Fantasy: Oñate on the Lower Colorado River, 1604-1605. Southern California Quarterly 86(4), in press.

Love, Bruce, and Marian Dahdul

2002 Desert Chronologies and the Archaic Period in the Coachella Valley.

Pacific Coast Archaeology Society Quartery, in press.

Meigs, Peveril, III

1977 Notes on the Paipai of San Isidoro, Baja California. Pacific Coast

Archaeological Society Quarterly 13(1):11-20.

Mixco, Mauricio J.

1977 Textos para la etnohistoria en la frontera dominicana de Baja California.

Tlalocan 7:205-226.

1978 Cochimí and Proto-Yuman: Lexical and Syntactic Evidence for

a New Language Family in Lower California. University of Utah Anthropological

Papers No. 101. Salt Lake City.

Ochoa Zazueta, Jesús Ángel

1982 Sociolingüística de Baja California. Universidad de Occidente,

Los Mochis, Mexico.

O'Connell, James F.

1971 Recent Prehistoric Environments in Interior Southern California.

University of California, Los Angeles, Archaeological Survey Annual Report

13:173-184.

Robles Uribe, Carlos

1965 Investigación lingüística sobre los grupos indígenas

del estado de Baja California, México. Anales del Instituto Nacional

de Antropología e Historia 17:275-301.

Rogers, Malcolm J.

1939 Early Lithic Industries of the Lower Basin of the Colorado River

and Adjacent Desert Areas. San Diego Museum Papers No. 3. San Diego.

1945 An Outline of Yuman Prehistory. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 1:167-198.

Schaefer, Jerry

1986 Late Prehistoric Adaptations during the Final Recessions of Lake

Cahuilla: Fish Camps and Quarries on West Mesa, Imperial County, California.

Mooney-Levine and Associates, San Diego.

1994 The Challenge of Archaeological Research in the Colorado Desert: Recent Approaches and Discoveries. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 16:60-80.

Schaefer, Jerry, Lowell J. Bean, and C. Michael Elling

1987 Settlement and Subsistence at San Sebastian: A Desert Oasis on San

Felipe Creek, Imperial County, California. Brian F. Mooney Associates,

San Diego.

Schaefer, Jerry, and Gary Huckleberry

1995 Evidence of Agriculture and Irrigation at Tahquitz Canyon. In Archaeological,

Ethnographic, and Ethnohistoric Investigtions at Tahquitz Canyon, Palm

Springs, California, by Lowell John Bean, Jerry Schaefer, and Sylvia Brakke

Vane, Chapter 20. Cultural Systems Research, Menlo Park, California.

Schroeder, Albert H.

1981 Discussion. In The Protohistoric Period in the North American Southwest,

AD 1450-1700, edited by David R. Wilcox and W. Bruce Masse, pp. 198-208.

Arizona State University Anthropological Research Papers No. 24. Tempe.

Seiler, Hansjakob

1977 Cahuilla Grammar. Malki Museum Press, Banning, California.

Shackley, M. Steven

1983 Late Prehistoric Agave Resource Procurement and a Broad-Spectrum

Subsistence Economy in the Mountain Springs Area, Western Imperial County,

California. Paper presented at the 17th annual meeting of the Society

for California Archaeology.

1984 Archaeological Investigations in the Western Colorado Desert: A Socioecological Approach. Wirth Environmental Services, San Diego.

Shipek, Florence C.

1982 Kumeyaay Socio-Political Structure. Journal of California and Great

Basin Anthropology 4:296-303.

1986 The Impact of Europeans upon Kumeyaay Culture. In The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Local Native Americans, edited by Raymond Starr, pp. 13-25. Cabrillo Historical Association, San Diego.

1993 Kumeyaay Plant Husbandry: Fire, Water, and Erosion Management Systems. In Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians, edited by Thomas C. Blackburn and Kat Anderson, pp. 379-388. Ballena Press, Menlo Park, California.

Spier, Leslie

1933 Yuman Tribes of the Gila River. University of Chicago Press. Chicago.

Stone, Connie L.

1981 Economy and Warfare along the Lower Colorado River. In The Protohistoric

Period in the North American Southwest, AD 1450-1700, edited by David

R. Wilcox and W. Bruce Masse, pp. 183-197. Arizona State University Anthropological

Research Papers No. 24. Tempe.

Strong, William Duncan

1929 Aboriginal Society in Southern California. University of California

Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 26:1-358. Berkeley.

Sutton, Mark Q., and Philip J. Wilke (editors)

1988 Archaeological Investigations at CA-RIV-1179, CA-RIV-2823, and CA-RIV-2827,

La Quinta, Riverside County, California. Coyote Press Archives of California

Prehistory No. 20. Salinas, California.

True, D. L.

1970 Investigations of a Late Prehistoric Complex in Cuyamaca Rancho State

Park, San Diego County, California. Archaeological Survey Monograph. University

of California, Los Angeles.

Waters, Michael R.

1980 Lake Cahuilla: Late Quaternary History of the Salton Trough, California.

Unpublished Master's thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson.

1982 The Lowland Patayan Ceramic Tradition. In Hohokam and Patayan: Prehistory

of Southwestern Arizona, edited by Randall H. McGuire and Michael B. Schiffer,

pp. 275-297. Academic Press, New York.

1983 Late Holocene Lacustrine Chronology and Archaeology of Ancient Lake

Cahuilla, California. Quaternary Research 19:373-387.

Weide, David L.

1976 Regional Environmental History of the Yuha Desert. In Background

to Prehistory of the Yuha Desert Region, edited by Philip J. Wilke, pp.

9-20. Ballena Press Anthropological Papers No. 5. Ramona, California.

Weide, Margaret L.

1976 A Cultural Sequence for the Yuha Desert. In Background to Prehistory

of the Yuha Desert Region, edited by Philip J. Wilke, pp. 81-94. Ballena

Press Anthropological Papers No. 5. Ramona, California.

White, Chris

1974 Lower Colorado River Area Aboriginal Warfare and Alliance Dynamics.

In 'Antap: California Indian Political and Economic Organization, edited

by Lowell John Bean and Thomas F. King, pp. 111-135. Ballena Press Anthropological

Papers No. 2. Ramona, California.

White, Raymond C.

1963 Luiseño Social Organization. University of California Publications

in American Archaeology and Ethnology 48:91-194. Berkeley.

Wilke, Philip J.

1974 Settlement and Subsistence at Perris Reservoir: A Summary of Archaeological

Investigations. In Perris Reservoir Archaeology: Late Prehistoric Demographic

Change in Southeastern California, edited by James F. O'Connell, Philip

J. Wilke, Thomas F. King, and Carol L. Mix, pp. 20-29. California Department

of Parks and Recreation Reports No. 14. Sacramento.

1978 Late Prehistoric Human Ecology at Lake Cahuilla, Coachella Valley, California. Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility No. 38. Berkeley.

Wilke, Philip J., Thomas W. Whitaker, and Eugene Hattori

1977 Prehistoric Squash (Cucurbita pepo L.) from the Salton Basin. Journal

of California Anthropology 4:55-59.

Wilken Robertson, Miguel

1993 Una separación artificial: grupos yumanos de México

y Estados Unidos. Estudios Fronterizos 31/32:135-159.

Winter, Werner

1967 The Identity of the Paipai (Akwa?ala). In Studies in Southwestern

Ethnolinguistics: Meaning and History in the Languages of the American

Southwest, edited by Dell H. Hymes and William E. Bittle, pp. 371-378.

Mouton, The Hague.