Home

Mission Statement

Editorial Policy

Submission Information

Volume One

Casual Papers

Fort Guijarros

Volume Two

San Diego State College Historic District: The Mediterranean Monastery as a College Campus

Lynne E. Christenson, Alexander D. Bevil, and Sue Wade

Introduction

San Diego State University’s Historic District is an important and unique representation of evolving twentieth-century educational philosophies, architecture, and the significant accomplishments of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Southern California. The district’s plan, layout, and design are directly associated with the goals of the early leaders of this institution who sought to move its educational philosophy from that of a curriculum based on rote memorization and drill to a more holistic approach of educating and developing the complete person’s mind and body. Under the direction of these visionary presidents, San Diego Teachers College developed into a comprehensive modern university with the Historic District as its core, and this district remains the symbolic center of San Diego State University today.

Educational Foundations of a University

What is today San Diego State University began as the San Diego Normal

School, established in 1897 to provide local education for future female

elementary school teachers (Starr 1995:18). The term originated in eighteenth-century

France from the École Normale Supérieure (“Normal

Superior School”), established in Paris in 1794 as a model for teacher

training schools. Although the state legislatures both established schools

and controlled their number and placement, the organization, curriculum,

and management of the schools depended upon local needs. Thus, the presidents

of the normal schools were highly varied and had a marked personal influence

(Harper 1939:103). Some traditionalists argued that teachers only needed

to learn those topics that would “normally” be taught in an

elementary school. However, this attitude was not shared by Dr. Edward

L. Hardy, the second President of what was then San Diego Normal School.

During his 25 years in office, the institution evolved into the San Diego

State Teachers College in 1923, and then the San Diego State College in

1935 (Starr 1995:91). Hardy’s vision “lifted the normal school

from a narrow training in pedagogical methods and teaching skills to a

concept of broad professional preparation and academic enrichment for

the teacher" (Lesley 1947:22). A progressive educator and administrator,

Hardy influenced higher education throughout California and was instrumental

in raising the standard of the profession of teaching during the early

20th century (Love 1955:52).

Hardy’s views regarding the nature of education showed the influence

of the Herbartian education movement, which held that the traditional

method of teaching through rote, memory, and drill was not effective.

Herbartian education preached the doctrine of interest: students should

be interested in the subject and also develop interests (Harper 1939:127).

Hardy was also a strong advocate of women's abilities long before this

was a popular sentiment. He recognized that those professions usually

filled by men such as engineer, lawyer, and minister required more than

two years of college education. Teachers’ training, however, was

limited to the basics and seen as a "preparation for spinsterhood"

(Lesley 1947:24). The business of professional preparation for teachers

was solely in the hands of the normal schools, as existing universities

and colleges often felt that such training diminished the true work of

the university. Hardy felt the need to expand the educational opportunities

for teachers, and developed curricula to accomplish this (Lesley 1947;

Starr 1995).

Following these designs, Hardy forwarded the inclusion of the laboratory

phase of teacher education, which was adopted at San Diego Normal School.

Advocates of such laboratory or practice schools felt that normal schools

should duplicate as closely as possible those conditions that a teacher

would encounter in the field. This would also allow model and experimental

schools to demonstrate new and better teaching techniques. Hardy assured

the continuation of the laboratory method by designating a Teacher Training

building in the new college design (Lesley 1947:24-25). Along with the

laboratory phase, Hardy believed that many extra curricular activities

should be incorporated as an official part of the development of teachers.

Normal schools pioneered the incorporation of drama, music, and physical

education activities into curricula (Harper 1939:119). Future construction

of the Little Theater as well as the Gymnasium, Aztec Stadium, and Greek

Bowl assured that drama, music and sports would be part of the new campus’s

curriculum at San Diego State Teacher’s College (Lesley 1947:25-26).

Building a New College from the Ground Up

The years 1921 to 1935 were marked by great change at San Diego State

Teachers College; it was during this time that President Hardy's vision

and philosophy came to fruition. The enrollment increased from 600 students

in 1921 to 1,300 in 1925, consistent with the overall growth in college

enrollment nationwide (Lesley 1947:40-41). Due to this increase, the state

granted San Diego State Teachers College status as a four-year institution

in 1923. Since the 25-year-old University Heights campus would not be

able to sustain a larger student population, Hardy began planning for

a new and larger school to accommodate the increase in students. He envisioned

the New San Diego State Teachers College campus as a “harmonious

expression of learning and architecture” with allegorical architectural

links to “historic institutions of civilization and enlightenment”

(Hardy 1929:1). On April 6, 1928, the Citizen’s Executive Committee

chose to locate the new campus in the center of a 125-acre site in the

heart of the newly subdivided Mission Palisades tract in San Diego (Bevil

1995:41).

One of several potential locations, the Mission Palisades or “Bell-Lloyd”

site was a gift from Los Angeles oil tycoon Alphonzo E. Bell, through

the aegis of his Bell-Lloyd Investment Company (Bevil 1995:42). Located

approximately seven miles due east of the old University Heights campus,

the new site’s advantages included a level building area, two arroyos

suitable for construction of an athletic stadium and amphitheater, an

unobstructed view of the surrounding area, and room for expansion. The

Bell-Lloyd Company contributed the services of its landscape architect

and urban planner, Mark Daniels, and $50,000 to the campus building fund

for grounds improvement (Bevil 1995:42). The following May, the voters

of San Diego approved a bond issue to purchase the old Normal School site.

Students, faculty, and distinguished visitors attended the October 7,

1929 groundbreaking ceremonies, which included speeches, live music, and

a ceremonial flag-raising (Starr 1995:73). Two years later, the first

classes were held on February 9, 1931, and the first graduating class

numbered about 90. Although far from complete, the new campus’ landscaping

and architectural embellishment indicated that San Diego State Teacher’s

College would be “one of the most beautiful of the Pacific Coast

colleges” (Bevil 1995:43-44; Lesley 1947:48-9). All of this would

become the nucleus of the present historic district (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Aerial view of San Diego State Teacher’s College taken in 1931. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Both the physical size and the reputation of San Diego State Teacher’s

College grew during these years. Evidence of its stature among colleges

can be seen in two 1934 events which took place at the new campus. The

San Diego State student body president was host to all student body presidents

of colleges west of the Rocky Mountains, the first time this enclave had

been held at a State college (Lesley 1947:55). In November of 1934, the

International Relations Club was host to the Third Annual Pacific-Southwest

International Relations Club conference. Speakers included a member of

the Carnegie Institute and a former president of Mexico (Lesley 1947:56).

Under Hardy's leadership, San Diego State Teachers College had gained

the recognition, prestige, and professionalism he always felt it deserved.

In 1935 the California State Legislature dropped the term "Teacher"

from the title of the State colleges, and San Diego State College was

born (Lesley 1947:56). In addition to the name change, the legislature

encouraged colleges to add liberal arts classes to their curricula. With

this as the culmination of his life's work, President Hardy retired from

San Diego State (Lesley 1947:57; Starr 1995:91).

The College Expands under New Leadership

Dr. Walter R. Hepner was the third president of San Diego State College.

Under Hepner’s administration (1935-1952), San Diego State became

a full-fledged academic institution. In 1935 the California State Legislature

authorized the expansion of the college through offering degree programs

other than teacher preparation (Lesley 1947:57). Hepner believed that

San Diego State College should do more than prepare its graduates for

employment; he stressed that a good liberal arts background was necessary

preparation for success in life (Starr 1995:92). Student enrollment increased

dramatically during Hepner's administration, and in order to meet the

demand of increasing campus population, it was necessary to plan for the

future expansion of the campus (Starr 1995). During his tenure, Hepner

was responsible for coordinating the building of eight new buildings,

building extensions, and adding acreage to the original campus with the

help of WPA workers (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 A view of the expanded campus in 1948. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Hepner also coordinated the preparation of the campus educational programs to meet the wartime demands during World War II. During this time, over 114 acres were added to the campus (Bevil 1995: 57).

Architectural Style of the Historic District

Constructed over a period of thirteen years from 1930 until 1943, the

historic campus core buildings and grounds represent the evolution of

the Spanish Colonial style in Southern California. Their historic design

and layout are linked directly to the visionary mindset and educational

philosophy of President Hardy, which he detailed in popular magazines

of the time (Hardy 1930). Hardy explained in that the style of a building

affects one’s feeling toward life, noting that “civilization

is a . . . social work of art, expressed in social action, like a ritual,

or a play (Hardy 1929:3). Overall, Hardy insisted that “the new

State College of San Diego [be designed] in architecture reminiscent of

Spain . . ., influenced by the Arabian and Moorish . . . in a landscaping

very like that of southern Spain” (Hardy 1929:3).

The Spanish Colonial Revival Architectural Movement in Southern

California

Two interrelated architectural styles—Mission Revival and Spanish

Colonial Revival—were extremely popular in California and throughout

the United States between the two world wars. Using these styles, California’s

predominant white middle-class society sought to establish a uniquely

Californian architectural identity during the early part of the 20th century.

However, instead of creating a truly original style, they focused on reinventing

a romanticized version of its Hispanic past (Bevil 1995:44). The first

attempts at rediscovering California’s architectural Hispanic past—the

Mission Revival Style (1890-1915) —was the first phase of the Spanish

Colonial Revival (Gebhard 1997). It drew upon original late 18th to early

19th-century Spanish Mission architecture, using design and construction

features dating back to the beginnings of Spanish vernacular architecture.

Some of its most distinctive architectural characteristics included massive,

unadorned, whitewashed walls constructed of sun-fired adobe bricks, roofs

of red, fired clay tiles with overhanging eaves, and floors of red square

tiles (Bevil 1992). Other unique architectural features commonly associated

with Southern California missions include a built-in or free-standing

campanario, or pierced wall bell tower, a curving ornamental false front,

and one or more arcaded walks. Patios with fountains were also common

(Gebhard 1967, Weitze 1984).

The Spanish Colonial Revival style developed concurrently with the Mission

Revival style. Although incorporating design features found in the Spanish

missions, its promoters also looked toward Moorish, Italian, and Pueblo

Indian antecedents for architectural inspiration. Also known as the Spanish

Eclectic or Mediterranean Revival, its characteistics include a combination

of details from several eras of Spanish, Mexican, and Southwestern territorial

United States architecture (Gebhard 1997). Similar to the Mission Revival,

the style featured roofs covered with barrel-shaped Mission or S-shaped

“Spanish” fired clay tiles. Doors and doorways contained dramatic

carved wood door panels and molded concrete or art stone spiral columns

and pilasters, carved stonework, and geometrically patterned colored faience

tiles. Window openings were either multi-arched or parabolic, employing

grills of wood, iron, or concrete. Other details typically included whimsical

tile-roofed chimney tops, brick or tile vents, mosaic tile-covered fountains,

arcaded walkways, and round or square towers (Requa 1926; McAlester 1984:418).

The Spanish Colonial Revival as Manifested in the Historic

Campus Core District

The San Diego State College Historic District is a singular and outstanding

example of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture in an institutional setting.

Relatively intact to this day, the core buildings are invaluable sources

for studying the most desirable elements of the Spanish Colonial Revival

architectural style adapted to a Southern California college campus. The

historic core campus buildings express one of the style’s best features:

restraint and sophistication. The buildings represent sculptural volumes

that are “closely attached to the land, whereby the basic form of

the building was broken down into separate smaller shapes which informally

spread themselves over the site” (Gebhard 1967:137). While many

of the buildings contain elaborate detail, for the most part their exteriors

of smooth reinforced concrete and stucco walls imitating whitewashed adobe

walls present a somewhat austere expansive face. Offsetting this is the

placement of elaborate interior patios and gardens for movement between

classrooms, studious contemplation, and social interaction (Requa 1926;

McAlester 1984:418) This attention to the arrangement of volumes and open

spaces across the built landscape of the campus, with combinations of

flat, hipped, and gabled roofs, gave the impression of the multiple and

varied roof-lines of Spanish villages, or, in the case of San Diego State

Teachers College, the “harmonious expression of learning and architecture”

(Gebhard 1967:139; Hardy 1929:1).

The college’s chief designer, Howard Spencer Hazen, worked in a

style fusing Medieval Spanish Moorish, Jewish, and Christian architectural

styles, know as the Mudejar (Bevil 1995:45). This style uses the horseshoe

arch and the vault; in its native Spain it often includes wooden and ivory

ornamentation. Metalwork and ceramic elements are also present, which

can be seen in the example of the SDSU portales discussed below. The driving

force behind San Diego State Teachers College’s master plan was

to create a campus that resembled a sprawling Spanish/Moorish university

with arcaded walks and drought-resistant gardens. Situated on an isolated

ridge overlooking Mission Valley, the campus took the appearance of a

Mediterranean monastery built on a mountain to protect and shelter its

occupants from the corruptive influences of the outside world.

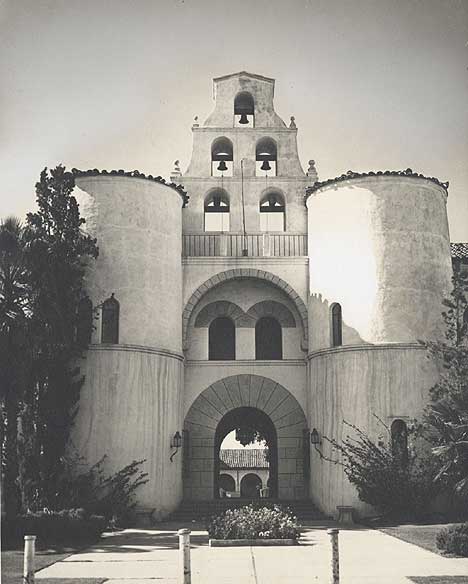

This “defensible space” metaphor can be seen readily in the

design of the Administration Building’s portales or main entry (Figure

3.3).

Figure 3.3 The portales of the administration building. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Resembling a heavily defended bastide style entryway, two 2-story barrel-shaped

turrets flank a Catalonian-inspired cut stone archway. Rajas (wrought-iron

window grills) and ajimezes (concrete window grates) add to the entry’s

defensive character. One of the most photographed buildings on campus,

the portales’ most interesting feature is the Mission-style campanario

(pierced bell tower) bridging the gap between the twin turrets’

red tile roofs. A noted architectural characteristic of Mediterranean

and Spanish Colonial church architecture, SDSU’s campanario is very

similar to those at Mission San Diego and at the Franciscan assistencia

or sub-mission at Pala east of Mission San Luis Rey. It is speculated

that the former may have influenced Hazen’s design (Bevil 1995:47,

56).

Through the south entrance portales, a Moorish-style wrought-iron lantern

hangs down the middle of a high ribbed arch vaulted ceiling. A band of

turquoise glazed faience tile (azuelos) extends around the interior walls.

Exiting the portales, a bead-trimmed stone archway opens out onto the

landscaped courtyard of the original campus commons. Although bare at

the time of the campus’ February 1931 opening, the commons’

original landscaping theme was to soften the stark white stucco walls

through the use of foundation plantings and ornamental trees placed throughout

the grass lawns. Conforming to the style’s passion for historical

allegory, Mark Daniels chose specific plant material that would do well

in San Diego’s hot, arid summer climate and heavy clay soil—conditions

very similar to the Mediterranean’s mountainous littoral regions

(Bevil 1995:47-48).

Figure 3.4 Hardy Tower as it appeared in 1959.Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

However, even drought-resistant plants, along with students and faculty,

get thirsty. Sanitary issues and fire protection also needed to be considered.

The solution was the placement of a 50,000-gallon water storage cistern

buried within the main quad area near the base of the Campanile. In reality

a camouflaged water tower, Hardy Tower contains a 5,000-gallon water tank

near its 200-foot apex (Figure 3.4). Electric pumps at the tower’s

base drove water up from the underground cistern to the upper tank. The

weight of the water and gravity then provided adequate “head pressure”

for the campus water supply system (Bevil 1995:49).

The Campanile also had an allegorical purpose; Hazen designed it and the

adjacent Library Building to suggest a Spanish Roman Catholic church building

and bell tower built by Moorish craftsmen. The building’s east wing,

with its sheltered arcades and spacious courtyards, resembles the cloistered

inner compound of Mission San Juan Capistrano. Such Mission era details

as grilled windows, wrought-iron fixtures and weather vanes on tiled cupolas

and hooded chimneys are found within this area of the quad. Both the adjacent

Science and Training School buildings continue this architectural allegory.

The diminutive patio within the former contains the “Banana Quad,”

cared for by grammar school children and their student teachers (Bevil

1995:49-50).

Scripps Cottage, originally located nearby the Campanile in the quad area

in front of what is now Love Library, resembles a vernacular Spanish Colonial

country house (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 Scripps Cottage in its original location. Courtesy of San Diego State

University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

The result of a $6,000 donation by local benefactress Ellen B. Scripps, it served as the headquarters of the campus Y.M.C.A. and Y.W.C.A. organizations as it does today in its new location near Scripps Terrace and HilltopWay (The Aztec, 23 September 1931). North of the cottage’s original location was the Aztec Café and Bookstore (Figure 3.6), also done in Spanish Eclectic vernacular style (Bevil 1995:51).

Figure 3.6 A view of the old bookstore with Hardy Tower in the background. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Even the utilitarian Shop and Boiler Building located on the campus’

northeast ridge overlooking Alvarado Canyon were built in the Spanish/Mediterranean

tradition. Housed within its “Shop Building Renaissance” design

were the oil-fired boilers that provided heat throughout the buildings

during the winter months (Bevil 1995:50).

The last building that Howard Hazen designed was the monumental Women’s

Gymnasium Building. Hazen continued the Mudejar-influenced design features

by incorporating ventanas geminadas on the gymnasium’s south facade

as he did on the Academic Building’s Admissions Wing. Spanish for

“twin windows,” they imitate those found in many Iberian and

Spanish Colonial-era buildings in Mexico. His signature work is the Gothic-inspired

southeast entrance portico on the gymnasium’s southeastern corner

with its floriated capitals supported by coupled columns. Another unique

feature of the steel frame and reinforced concrete-constructed “earthquake-proof”

building is its open garden patio court, with its central Moorish-influenced

fountain, decorated entryway, and red tile covered loggia (Figure 3.7).

Figure 3.7 The garden patio court of the Women’s Gym. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Provisions were made for a swimming pool on the east side of the gymnasium; however the budgetary concerns caused by the economic depression of the 1930s prevented its completion. Only concrete bleachers, now covered up, and a wing off the southeast portico, since demolished, were ever built (Bevil 1995:51).

The Role of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), 1935-1943

In the midst of all of this building, the effect of the Great Depression

was finally felt. Because of slow housing sales in the Bell-Lloyd/Mission

Palisades Tract, the Bell-Lloyd Company (the college benefactor) abandoned

the entire project in 1936, stifling San Diego State College's development.

Luckily, there was a mechanism in place that would help continue the campus

development into a stylized Spanish Colonial Revival-inspired educational

complex: the WPA (Bevil 1995:51-52). The WPA or Works Progress Administration

was a federally-funded program designed to provide work for a limited

number of unemployed Americans during the Great Depression. Part of the

Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, the WPA sought to provide

employment by initiating projects around the country (Howard 1973).

WPA-funded projects accepted skilled, semi-skilled, or unskilled workers,

with veterans and the widows of veterans given first priority (Howard

1973:329). The only limitations were that one had to be an American citizen,

18 years or older, and that only one member per household could be employed

at any given time. By the end of the program, between 25 and 30 million

workers benefited from WPA projects. With their skills and self-esteem

intact or increased, many later found jobs in private industry. The majority

of WPA projects were in construction, with 75% involved in either the

refurbishing or new construction of government buildings. The other 25%

of funding was directed toward a wide range of projects, ranging from

highway construction to the writing of books in Braille (Branton 1991:13).

Control of the various WPA projects was given to the local municipalities

in which they were located (Howard 1973). From its outset, San Diego's

public and private leaders were instrumental in formulating and sponsoring

projects that provided jobs which strengthened the city’s infrastructure.

Of the 19,650 people on relief in San Diego County in 1935, all but 4,000

(who were considered too old or infirm) were eligible for WPA jobs (Branton

1991:23). Two years later, WPA-funded construction projects in San Diego

were six times greater than elsewhere in the nation. San Diego County

benefited greatly from WPA projects which left a permanent legacy of many

fine buildings, structures, public art, and other projects throughout

the county (Branton 1991:132). The WPA played an essential part in the

building and expansion of San Diego State College through the depression

years. Although many of the initial core campus buildings were constructed

using funds that were allocated before the depression, by the mid-1930s

the college did not have the means to facilitate the increase in its student

population. The WPA-funded campus building projects helped President Hepner

continue the expansion of the campus as it was initially planned by Howard

Hazen, Mark Daniels, and Edward Hardy.

The first project approved for funding by the WPA was the building of

the Aztec Bowl football stadium (Figures 3.8 and 3.9).

Figure 3.8 WPA workers digging the Aztec Bowl on February 1, 1936. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Construction on the bowl provided work for between 300 and 700 men. Dug out of a natural geologic depression, most of the work was done by hand and with mule-powered grading equipment. At the time of its completion in 1936, the cobblestone and concrete Aztec Bowl was the only stadium built on any college campus in the state of California (Bevil 1995:57). Other WPA-funded campus construction projects included the building of a columned arcade between the Academic and Science Buildings, classroom annexes to existing buildings, the Greek Bowl (Open Air Theater), and nearly 100 wood and concrete benches lining the walkways within the quads (The San Diego State College Aztec [SDSCA], 26 October 1932:1).

Figure 3.9 WPA workers digging the Aztec Bowl on February 1, 1936. Courtesy of San Diego State University Library, University Archives, Photograph Collection.

Many lesser projects were also undertaken. Plans for a number of additional

buildings and improvements were complete by the end of 1940. However,

the need for national defense projects and the expansion of defense-related

industries in San Diego after 1940 shifted much of the manpower allocation

away from San Diego State (SDSCA, 3 March 1942:2). Only the Music Building

and extensions to the Library and Science Building were completed subsequent

to 1940 (Starr 1995:96). All three were dedicated on May 19, 1942 as part

of the college's forty-fifth anniversary celebration (Bevil 1995:57).

Support for the arts was also an important part of WPA-funded projects

in San Diego County (Mehren 1972). Artist Donal Hord was responsible for

sculpting "the Aztec" for San Diego State College. Sometimes

referred to as “Monty Montezuma,” it is a brooding statue

of an Aztec warrior cut from a single a 2.5-ton block of black diorite

(The San Diego Union [SDU] 30 April:1). While the WPA provided funds for

Hord’s salary, non-labor funding for tools and materials had to

come from private sources. The San Diego Art Guild and several local campus

student groups were among those who donated money. Five black and red

cans were distributed throughout campus. On Friday, February 28, 1936,

members of the Cap and Gown, Blue Key, and Oceotl societies made a final

push for students to contribute ten cents each so that sufficient funds

could be raised for the statue (The Aztec 26 February 1936:1). Hord and

his assistant Homer Dana completed the statue in 1937 (SDU, 30 April:1).

It was originally located at the entrance to the mall in front of Hepner

Hall, and in 1984 moved to the south entrance of the college (DeLory 2002).

Due to recent trolley construction, it is now located in the Prospective

Student Center.

Conclusion

The movement of “The Aztec” to make way for the new trolley

line becomes a metaphor for the campus Historic District in general: adjustments

must be made to accommodate the new. By the end of World War II, the Spanish

Colonial Revival style had lost favor. While certain elements of the Spanish

theme were incorporated into some of the buildings built between 1950

and 1970, the campus master plan has been continuously adapted and modified

to accommodate new buildings on campus reflecting architectural styles

currently en vogue. All of this produced a mélange of new buildings

throughout the campus by mixing buildings of different mass, scale and

architectural style (Bevil 1995: 52). However, San Diego State University’s

historic core campus buildings have survived into the 21st century, representing

a time of change and improvement which allowed a simple normal school

to transform into a comprehensive, modern, distinguished university.

References Cited

Bevil, Alexander

1995 From Grecian Columns to Spanish Towers: The Development of San Diego

State College, 1922-1953. Journal of San Diego History 41(1):38-57.

1992 The Sacred and the Profane: The Restoration of Mission San Diego

de Alcala 1866-1931. Journal of San Diego History 38(3).

Branton, Pamela Hart

1991 The Works Progress Administration in San Diego County, 1935-1943.

Masters Thesis, San Diego State University.

DeLory, Colleen.

2002 Aztec Statue Finds Home in New Prospective Student Center. Electronic

document, http://www.sdsuniverse.info/story.asp?id=1869, accessed January

7, 2006.

Gebhard, David

1967 The Spanish Colonial Revival in Southern California (1895-1930).

Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 26(2):131-147.

Hardy, Edward L.

1929 The New State College, In Which Bags and Bobs Will Blend with Historic

Architecture. San Diego Magazine. September:3.

1930 The City Within. The Modern Clubwoman July-August.

Harper, Charles A.

1939 A Century of Public Teacher Education. Hugh Birch-Horace Mann Fund

for the American Association of Teachers Colleges, Washington, D.C.

Howard, Donald S.

1973 The WPA and Federal Relief Policy. Da Capo Press, New York.

Kirker, Harold C.

1981 Old Forms in a New Land: California Architecture in Perspective.

Roberts Rinehart Publishers, Niwot, Colorado.

Lesley, Lewis, B.

1947 San Diego State College, the First Fifty Years, 1897-1947. San Diego

State College, San Diego, California.

Love, Malcolm A.

1955 San Diego State College - Service and Leadership in a Growing Community.

In The California State Colleges, pp. 50-59. California State Department

of Education, Sacramento, California.

McAlester, Virginia and Lee

1984 A Field Guide to American Houses. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Mehren, Peter

1972 Arts Were a Part of WPA, Too. San Diego Union 30 July:E1. San Diego,

California

“normal school”

2005 Encyclopedia Britannica Online, http://search.eb.com.libproxy.sdsu.edu/eb/article-9056136?query=normal%20school&ct=,

accessed December 5, 2005.

Requa, Richard S., A.I.A.

1926 Architectural Details, Spain and the Mediterranean. The Monolith

Portland Cement Company, Los Angeles.

San Diego State College Daily Aztec

1968 Landmark Relocated. 24 September.

San Diego Union

1937 Year of Work Required to Carve Aztec Statue. 30 April:1. San Diego,

California.

Starr, Raymond

1995 San Diego State University: A History in Word and Image, edited by

Harry Polkinhorn. San Diego State University Press, San Diego.

The Aztec

1931 Scripps Cottage to Be Dedicated. 23 September. San Diego, California.

1936 Art Guild Starts Dime Campaign for Hord Aztec Statue. 26 February.

San Diego, California.

Weitze, Karen J.

1984 California’s Mission Revival. Hennessey & Ingalls, Los

Angeles.