Home

Mission Statement

Editorial Policy

Submission Information

Volume One

Casual Papers

Fort Guijarros

Volume Two

A Field of Dreams: From San Diego State to Berkeley

M. Steven Shackley

When Seth asked me to write down some memories of my days in anthropology at San Diego State, I thought that this must be karma for making him work in the California archaeology collections in the Hearst (then Lowie) Museum at Berkeley. He has asked me to write a bit about my background that led me to SDSU, what that experience means to me now, and my thoughts about a four-field anthropology while teaching in a department that does not value that approach.

Some of us are fortunate to have stumbled upon a field of interest that keeps us intensely engaged throughout our careers. I began this odyssey many years ago as a child growing up in what was then a rural and arid area of eastern San Diego County called Jamacha, named for the rancheria where Delfina Cuero was born. It’s now called Rancho San Diego and exhibits the high aesthetic of those little box communities called the suburbs. I spent much of my pre-teen and teen years scouring the chaparral and desert hills engaging in that kind of childhood natural science that many of us in archaeology and geology experienced. At the time it would have been difficult for anyone, least of all me, to decide which academic course (if any) I would take.

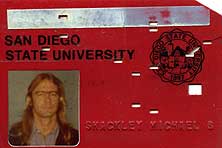

I began at San Diego State nearly 30 years ago, and much has changed for me and for your institution (Figures 5.1 and 5.2).

Figure 5.1 Shackley’s 1977 SDSU ID card. Courtesy of M. Steven Shackley.

Figure 5.2 A recent photograph of Shackley at the Antelope Creek locality

of the Mule Creek obsidian source in western New Mexico. Courtesy of M.

Steven Shackley.

I did not begin in anthropology. After a year in college I was drafted into the Marines during the late 1960s. After that “fun” experience, I used the GI Bill and applied to the geology programs at Cal Tech and the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, as well as San Diego State. I was accepted in geology/geochemistry at New Mexico and SDSU and decided on SDSU since I had begun a new family with roots in southern California. I had already taken my introductory courses in anthropology at Grossmont College before getting drafted, so I set aside anthropology in the beginning and concentrated instead on the geology department and my interest in volcanic petrology and raw materials. Then, in order to fulfill something akin to an American Cultures course, I took a class with Phil Staniford, and my life changed forever. I thought if a department could let a crazy guy like that teach, then there was hope for me! I remained friends with Phil for the rest of my time at SDSU until his untimely death, and although my interest or “specialty” was decidedly archaeological and geoarchaeological, the four-field approach at SDSU was very stimulating. In that regard, the four-field endeavor has shaped my career and my life. Most of my work has integrated all the fields, particularly archaeology, cultural anthropology, and linguistic anthropology.

While finishing my A.B. in the two fields, the SDSU anthropology department hired a new faculty member who specialized in the American Southwest and who was to arrive the next year. I began my M.A. degree while waiting for him to arrive, but unfortunately he was killed in a car accident; so I shifted interests to southern California topics. My thesis focused, in part, on the economic contacts between southern California and the North American Southwest with Joe Ball as chair, and Larry Leach and Ned Greenwood (Geography) as the committee. This thesis, finished in 1981, reappeared in 2004 when the University of California Press published a derivation of it entitled “The Early Ethnography of the Kumeyaay.” This work integrated much of that thesis, and was co-written with Steve Lucas, a Kumeyaay friend and colleague, whose grandfather I befriended while camping in the Laguna Mountains in the early 1960s.

It would be impossible to enumerate all the founding experiences of my

career that began at SDSU, but a few memories do rise to the top. For

humor, it would have to be Al Sonek. Between his alligator grin and bizarre

sense of humor, he often allowed me to see the reality in what seemed

an unbearable situation in class or with the administration. I was “running”

the archaeological clearinghouse with my good friend and colleague Jackson

Underwood. We were labeled as the cowboy archaeology grad students at

the time, and our office just around the corner from Sonek’s insured

that very little work would get done most days. Between Al and Jackson,

I got through the day and the M.A. program in two years.

Phil Greenfeld was my other source of amusement, both for his eccentricities

and his knowledge of the Southwest. Phil was my mentor and guide into

Phi Beta Kappa, and along with Larry Leach’s Southwest stories,

is probably most responsible for my interest in Southwest archaeology.

Recently, I have been working with Jane Hill on the linguistic anthropology

of the introduction of maize to the Southwest from Mexico. On a project

I directed at McEuen Cave in southeastern Arizona in 1997 and again in

2001, we recovered abundant maize and squash dating to over 4000 calibrated

years b.p. This was predicted by Jane decades ago based on her glottochronological

work with Tepiman and the larger Uto-Aztecan language family. I was able

to hold my own in conversing with Jane, certainly one of the Uto-Aztecan

experts in the field, because of my training in Ron Himes’ undergraduate

and graduate linguistic core courses.

To this day, much of my archaeological direction is influenced by Joe

Ball. My first formal field school was at the La Fleur Site in eastern

San Diego County, directed by Joe and Jenny. While I had quite a bit of

CRM experience, they both instilled in me the value of field and laboratory

research as the firm basis for any archaeology. I spent over 15 years

directing CRM archaeology projects in the American West, but I’ve

always seen CRM as a derivation of research archaeology, something I pass

on to my own students at Berkeley. This is not necessarily an opinion

shared by all our colleagues in North American archaeology, but like Joe,

when I’m certain of something, I stick to it. San Diego State is

lucky to have Joe, a respected Mesoamerican archaeologist who could have

worked anywhere, but stuck it out at SDSU.

So, what about the value and utility of a four-field anthropology? At

a time when so many North American anthropology departments are fissioning

into smaller parts, jettisoning linguistic anthropology, physical anthropology,

even archaeology, many of us, mostly archaeologists, lament this damaging

trend. Most of the younger social anthropologists we have hired at Berkeley

recently have come from graduate programs with ONLY social anthropology

core courses. Some have no physical, linguistic, or archaeological anthropology

at all. The March 2004 Society for American Archaeology Archaeological

Record devoted much of its content to this problem, at least from the

perspective of archaeology programs. Steadman Upham, a former graduate

student colleague at ASU, and now the President of the University of Tulsa,

notes that North American archaeology is vibrant and active, while many

social anthropology programs are mired in a confusing lack of direction

and extreme in-fighting. As a result, when campus administrators look

with some disdain on the entire department, archaeology gets painted with

the same broad brush and our programs suffer. Geoff Clark, my Ph.D. advisor

at ASU in the same issue blames, in part, the post-modern approach of

many social anthropologists and the abandonment of fieldwork as the basis

of any anthropology.

I think both Upham and Clark are partly correct, but as I talk to my younger

social anthropology colleagues, most of them seem to value a four-field

anthropology, even though they don’t really know what it is. So,

I’m not sure all blame can be laid upon a post-modern anthropology.

We have temporarily solved the problem at Berkeley by splitting into two

“houses”. Each house, archaeology and social anthropology,

has their own chair or house head, FTE budgets, and communicates to the

Dean directly. Undergraduates get a degree in anthropology, but the graduate

programs are separate. While this solves the issue of an effective and

highly regarded archaeology program being painted with that broad negative

brush, it isn’t solving the four-field problem. So, as a semi-independent

program, we are focusing our future hires on physical anthropologists,

linguistic anthropologists, and probably even ethnologists; three fields

generally rejected as anthropology by the other house. In this regard,

archaeology at Berkeley will begin to rebuild a four-field discipline.

Sadly, that will probably be the only way it will happen. We in the archaeology

program at Berkeley strongly believe that a 21st Century four-field anthropology

offers students and the world a discipline that is unique, encompassing,

and effective at dealing with many of the world’s problems, just

as it did in the 20th Century.

Frankly, the four-field training I received at SDSU has led me to where I am today. If I had gone through a single field program, I’m certain I would not be at one of the premier public universities doing an integrated anthropology. Finally, for those of my professors still at SDSU, I’ll be retiring in five or six years to a casa we’ve built in New Mexico where I’ve done fieldwork for nearly 25 years. This could make you feel old, but none of you seem to be slowing down. Anthropology is such a stimulant for all of us fortunate enough to have stumbled upon it as undergraduates. I frequently think of my time at SDSU, and am very proud of the education I received.

Berkeley, California

July 2005